Several state legislators participated in the Edmonds School District’s Town Hall on school funding on Oct. 23 at Edmonds-Woodway High School. The event was part of the Edmonds School District’s ongoing efforts to advocate for increased school funding after two consecutive years of painful budget cuts driven by several different factors mostly outside of the district’s control. Important programs like fifth grade band were cut entirely while athletics fees doubled from $100 to $200. State legislators representing areas from across the Edmonds School District were invited to speak to constituents about the current school funding crisis. District leadership made their case for increased school funding in front of thousands of supporters and dozens of legislatures. The budget issues are a result of a combination of factors, but mainly stem from decreased state funding for education. In 2019, about 52% of Washington state’s annual budget went to school; in 2023 this was 43%, representing a significant drop in school funding. Last school year, the legislature marginally increased the state’s allocation to individual students, but this only covered a small part of the Edmonds School District’s budget shortfall and other districts around the state that are also facing steep fiscal cliffs.

The school district got this point across by having several different teachers, students, and staff from across the school district talk about the current funding issues. One of the speakers was Meadowdale Middle School Principal Joe Weber, who said that the budget cuts were different than previous ones that didn’t contribute to larger class sizes and the cutting of important staff positions. He said that because of the cuts, teachers felt like they were failing students when it was really the legislature that failed students.

He also spoke on the McCleary Decision, which was a Washington State Supreme Court case that ruled that the Legislature wasn’t adequately funding education. The court ordered a new funding formula that increased total education funding, but reduced how much districts could take out in levies, hurting school districts like Edmonds that funded a large portion of education through levies. “McCleary leveled the playing field by underfunding everybody,” Weber said.

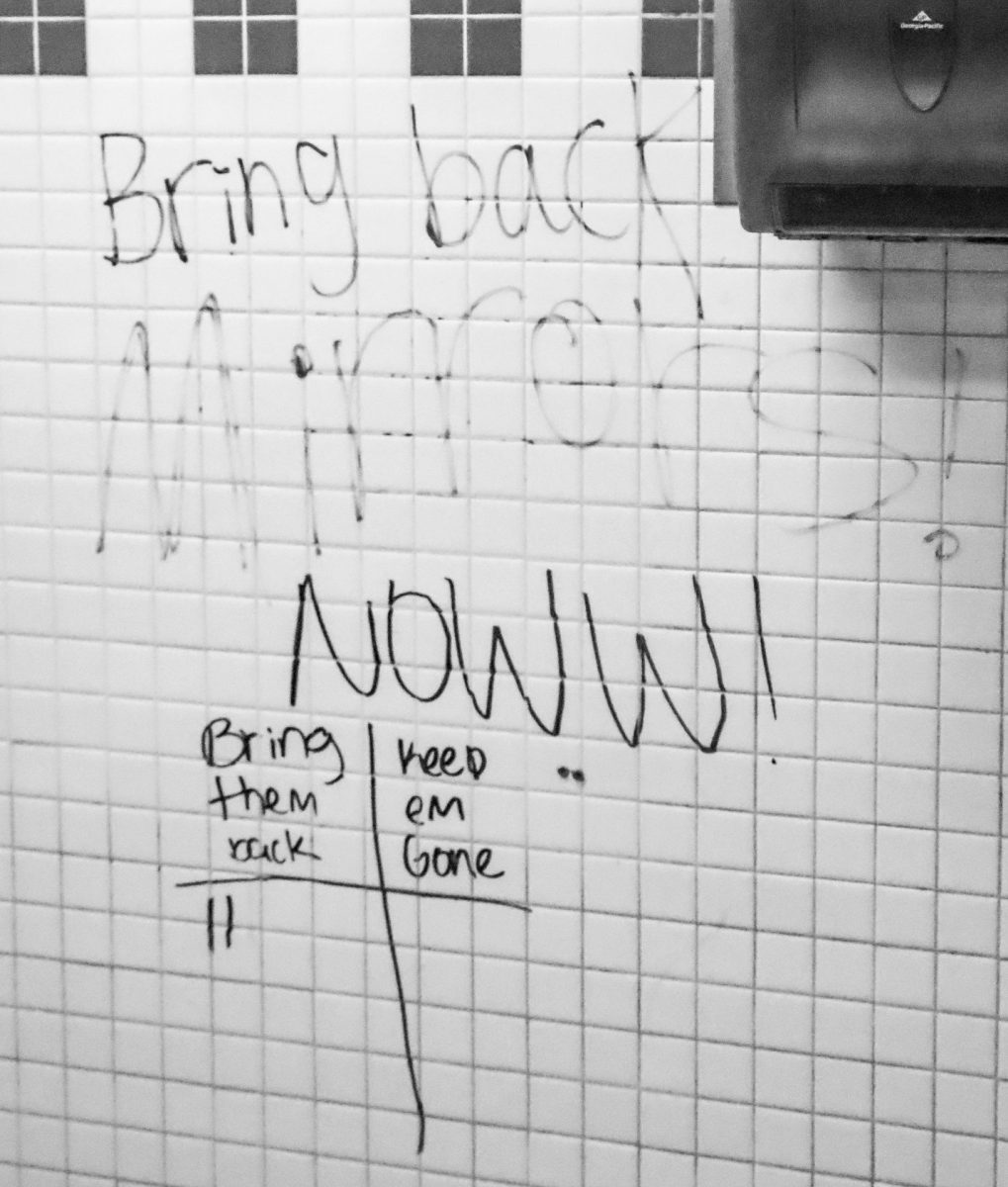

Another speaker was Edmonds-Woodway senior Mio Masunaga, who said that for a school to be successful, it must have a strong community surrounding it, adding that the budget cuts had hurt this sense of community through the elimination of programs.

While not being the main speaker, School Board Member Nancy Katims also spoke, using the example of pre-K child named Riley. Riley could be a future Edmonds School District student who would end being negatively affected by the districts’ budget cuts, which totaled around $10 million for the current school year.

Legislators were assigned to breakout rooms where they were tasked with answering questions from constituents about school funding.

During the breakout sessions, legislators were asked why they failed to increase school funding and why its total percentage in the state budget has decreased over the previous years. State Sen. Derek Stanford said that the K-12 funding going down as an overall percentage of the state government was more a result of the legislature funding more social programs paid for by new taxes than educational funding going down. “I think that the overall percentage has dropped because we’ve made bigger investments in safety net programs, primarily driven by a desire to support kids who need access to health care, housing, things like that, which I think is important to consider in the view of the students. But at the same time, I believe that we have fallen behind where we should be on investing in education.”

State Superintendent of Public Instruction Chris Reykdal said that education had been beaten out by other funding priorities the legislature saw as important during COVID, leading the system to rely on pandemic funds that eventually ran out. “I think they made a lot of progress going into the pandemic and then when there’s so many needs they told K-12 you rely on your federal money, your one time emergency money, we’ll give to you later, and they dealt with a lot of other challenges and I know how hard the job is,” Reykdal said. “We were able to get by with some federal money, but now it’s gone and it’s spent and now they have to really double down.”

Reykdal also talked about the 24 credit system. The state increased the number of credits required from 20 to 24 without increasing funding, limiting options for students. “I think the biggest impact is students have lost choices particularly in their junior year. They used to have a lot of electives their senior year, but it kind of ate up their junior year. I’d like to see a rigorous diploma, but choices within those 24 credits instead of prescribing so many of them. I’m not sure it’s a funding problem so much as it was that students lost a lot of control over their own destiny.”

On the November ballot, there were two initiatives that could’ve affected school funding were placed on the ballot. These were Initiative 2109, which would’ve repealed the state’s capital gains tax on individuals with over $250,000 gains; and Initiative 2117, which would’ve repealed the state’s carbon cap and trades scheme. Both of these ultimately failed at the ballot box, but according to Stanford, if passed, their effect on education funding would’ve been disastrous. “If we lose the capital gains tax, that would send a signal that voters do not want to make new investments in education funding, which I think would be terrible, and it would really have a chilling effect on efforts to raise any new revenue to fund education.”

Reykdal shared similar opinions, talking more about the funding sources to education derived from the tax. “The first $500 million goes to early learning, so it’s preparing our littlest learners for success. It’s the spillage over $500 million that goes to the capital budget and then immediately helps our school construction budgets. So, if you’re in a rural community and you can’t build a school because you can’t afford it, You don’t have the property tax bas, 60% on the [bond], there’s a base for you and ironically, the political leaders in those communities are the most opposed to the capital gains even though its doing the most to fund their schools.”

As a result of current school funding being inadequate, some have proposed suing the state again to force the legislature to fully fund education. However, Reykdal said this was an unlikely proposition. “I don’t think it’s imminent. We have this ambitious vision for what schools should be but the first billion is really the constitutional mandates – special ed, transportation, and inflation. And I think if they make enough progress on that, I don’t a court case is imminent ; If they don’t, I think there are a lot of people ready to get this back in the courts,” he said.

Stanford said that he wanted to avoid having to resolve this through the court. “It’s always possible that someone could take a case again, and might have that result again of going to the Supreme Court. I’m not sure how long it would take to get through that process, but I do think that that’s a possibility that the legislators are aware of that if the funding is not sufficient and continues that way, then certainly I would expect someone to bring another case like that,” Stanford said. “I don’t want us to go that route. I want us to just make good funding decisions to start with and then not have to worry about that.”

Even though the state failed to significantly raise school funding last legislative session, Stanford took a more hopeful note to funding next session. “I expect that even though we’re facing a deficit right now, I expect that we will be doing something to increase education funding. The question will be how much and that’ll be a question that everyone will probably have their own opinion about, whether it is enough or not, depending on how far we get, but that’s my goal, is to have that increase be significant, something that can put us back on the right track.”

Special education funding has not been funded as part of basic education in the past, leading school districts to fund services through levies. This has further contributed to districts budget shortfalls, as special education costs have grown significantly faster than general education costs post-COVID. Stanford said that this was more or less a symptom of the larger problem of education funding as a whole. “Overall, I’d say special education has had the same problem that all these other areas have had with education. We’re just not getting the job done,” he said.