On Dec. 7, 2018, at Lake Brantley High School (LBHS) in Altamonte Spring, Florida., students were at lunch when the intercom announced a “Code Red” drill, simulating an active shooter lockdown. The only issue: there was no indication of it being a drill, sending students into a panicked frenzy.

According to the Orlando Sentinel, teachers at LBHS were also unaware that the Code Red was a drill when they received a text message reading “Active Shooter reported at Brantley / Building 1/ Building 2 and other buildings by B Shafer at 10:21:45. Initiate a Code Red Lockdown.”

The lockdown lasted about an hour before the school’s administration clarified on Facebook that it was just a drill — that the threat was not real. Since the lockdown, the Seminole County Public School District has changed its policy and no longer performs this type of drill.

According to local NBC affiliate WESH2 News, students were blamed for the panic, while the students, “believe that miscommunication about a message that went out of the loudspeaker at lunch is to blame.”

This want for blame and sense of terror sounded all to familiar to me. I thought that MTHS was an outlier in this, and maybe it was at that time. But not anymore.

I was already at school on June 7, 2018, when I got an influx of messages on Snapchat from fellow MTHS students. The messages all relayed the same macabre information:

“There was a shooting threat against the school.”

Of course, I didn’t take it completely seriously with the numerous threats and fire alarms that had already happened that week. But this one felt a little different. People were already signing out and going home. Many more would do so later.

It felt different from the rumors of a threat from earlier that week or even earlier that year. It was more serious than the etching of a weapon above the date “6/5/18” into the boys bathroom stalls. It felt more real than the photo of bullets with an added caption of “watch out terrace’ spread around the MTHS community on January 4th, 2017. It felt more dangerous than the time when a student brought a pellet gun to MTHS on January 6th, 2017.

There were multiple times being said around the students for the alleged shooting. I remember people saying 11:11 a.m., people saying 11:14 a.m. and 11:20 a.m., placing the time during the passing period between first lunch and fourth period.

I sat in room 130 with several other Hawkeye staff members during lunch and no matter how familiar the faces were, I was still uncomfortable.

We sat there and talked about how likely the threat was to be real and we all determined there was no way it was real; there was no way someone would enter MTHS with a gun in a few minutes, especially after the rumors of the shooting had been spread. Yet, when that bell rang to go to fourth period, we all sat there in silence, looking at each other, waiting for someone to move. I can’t remember if anyone did, I just remember the eyes and a lot of confliction. We calmly decided there was no way this was real, yet the slight chance that it was real caused us to stay — at least caused me to stay.

At 11:14 a.m., Peter Schurke’s voice rang over the speakers: “We are going into a full lockdown.”

I ran into the dark room, thinking it would be the least likely place to get caught. A couple of strangers were in there as well. I later learned that some other Hawkeye students had pulled some students out of the hallway and into room 130. Another Hawkeye student came in and pulled us out of the dark room and into the studio around the corner.

There were 14 of us in there, sitting on the floor, crowded together in the dark. We had to keep the door cracked open to hear the announcements, warning signs or shots.

I was trying to calm down, but in the process I was invalidating my fear, thinking it was unnecessary. I felt stupid for being scared, but I couldn’t help it.

School shootings are real and all too common.

Most of us had our phones out and were recording. The videos that are still on my phone show all of our names being recorded on a video and written on a paper. One video showed my friend shaking while texting her parents that she loved them and she was sorry for going to school that day. The audio revealed whispering, shrill breaths and crying.

And then, after being stuck in that room for what felt like hours, the lockdown was lifted and an announcement on the intercom told us to go back to class. Unless your teachers said anything, that was it, it was over.

I remember thinking that it didn’t affect me, but when I saw someone running down the hall, I instinctively ducked down. When a student in my fifth period joked about it, I broke down in anger and fear.

For days afterwards, I had anxiety about entering MTHS and would have to leave early due to breakdowns. It was the most vulnerable I had ever felt at school and I still am affected by the anxiety from that day.

There was only one other student who attended the community forum on June 8, 2018. While there, I questioned the administration and police about the lockdown.

Why didn’t we go into lockdown at the earliest sign of a threat? Why don’t teachers actively participate in drills and what will you do to change that? Why don’t I know how to barricade a door? Why aren’t students directly taught what to do in the case of an active shooter? We didn’t have an adult in that room that day and not a single one of us knew what to do if something bad was actually happening. Why not?

Students from Lynnwood High School have told me that they have full-on ALICE drills, with an administrator walking down the halls and teachers over the intercom. Why are we not as prepared as other schools in our district when we get just as many threats, if not more?

There were very few answers—only confusion and surprise. That’s not enough.

People place the blame on different groups: the students, the parents’ Facebook group, the administration. Many parents at the community forum weren’t even looking for answers. They were wanting to know how they could help the school so this didn’t happen again.

Who knows if anyone followed through?

I’m finally seeing the effects of that day in and out of school. I’ve been told by administration that me speaking up about my experience affected them and they were working on solutions. I know they’ve attempted to start communicating to students when the lockdown is a drill. There’s still a lot to do, but it’s a start for sure.

No other student should have to go through what MTHS students did last June or what LBHS students experienced last December. But that means we need to talk about it. We need to talk about school shootings. We need to look at the statistics that show around the world what the solution to ending gun violence is.

There were 25 school shootings resulting in death last year alone. The Washington Post reported that since Columbine in 1999, more than 220,000 students have experienced gun violence at school. They also stated that 2018 has been an outlier with more shootings, more students affected and more deaths.

On Dec. 10, 2018, Vox compiled the numbers of school shootings and the number of deaths as a result,, Ffrom 1970-2018. Last year set the record high in school gun violence incidents and deaths as a result of school shootings; these are not the type of goals we should be setting for ourselves. With 94 school gun violence incidents and 55 people killed in those incidents, 2018 was the deadliest year to be in school.

We have seen the results of gun reform around the world.

Be involved, don’t ignore your feelings, but look at the statistics. Take a close look at our reality and make informed, educated decisions.

Gun Violence Archive, a website that was created to “document incidents of gun violence and gun crime nationally to provide independent, verified data” to the public, states that in 2018 there were 56,953 people injured or killed by gun violence in all of the United States.

According to NPR, the United States had an average of 3.85 gun deaths per 100,000 people in 2016, making us eight times more deadly than Canada and over 96 times more deadly than Japan when it comes to guns.

There is a large push in the United States to have universal background checks on people who are wanting to purchase a gun. Everytown for Gun Safety states that 85 percent of voters are in support of background checks. They also said that when Connecticut passed a background check law, they saw significant decreases in homicide and suicide rates by gun violence.

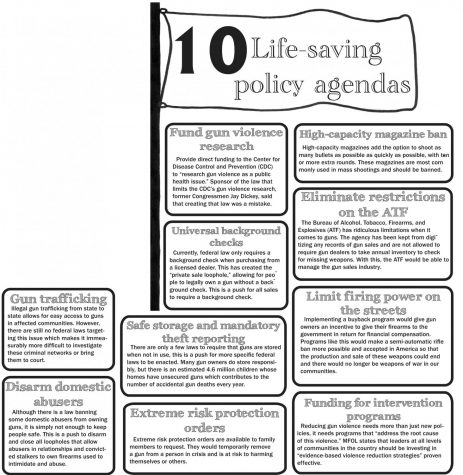

March For Our Lives has 10 specific policy agendas to fight for, and there are many people creating bills for these issues around the country. There is a way to fix this, and these 10 policy changes could be what we need to go it.

The ball is in our court—let’s use it. I’ve marched for our lives. I’ve protested. I’ve walked out. I’ve spoken my truths on the issue and now that I’m 18, I’m going to vote for it too.

The 10 policies from the March for Our Lives Policy Agenda listed on their website, stating that “here are ten policies proven to save lives — policies we need to accomplish as soon as possible to ensure the safety of our schools, homes and communities.” Clark hopes that these policies will remove fear just as well.