The Cascadia region is one that is blessed by the Earth. Replete with stoic mountains, scenic ocean views, majestic canyons and tranquil forest scenes, our beautiful, fertile neck of the woods is blissfully free from many dangers that afflict other parts of the world. Our wildlife is largely docile, we rarely see tornadoes or hurricanes, and our climes are mild and forgiving.

But beneath our feet, our normally-peaceful planet roils. The extreme temperatures within the earth bend and bow the very bedrock upon which we stand. The ground groans and stresses and builds up pressure – until it breaks.

Scientists have, of course, known about this for several decades. They call it plate tectonics. Although the idea of continental drift, a key part of the tectonic theory, was notably proposed in 1915 by Alfred Wegener, it took until the 1970s for various ideas and theories to come together as the modern practice of seismology.

Seismology is a field of particular interest on the west coast, where large faults, such as the San Andreas, run relatively close to major population centers.

One such fault is the Cascadia Subduction Zone (CSZ), which lies off the coast of Washington and Oregon. Here, the Juan de Fuca plate, a remnant of the once-vast Farallon plate which once underlaid the Pacific Ocean, slides beneath the North American plate by three centimeters per year.

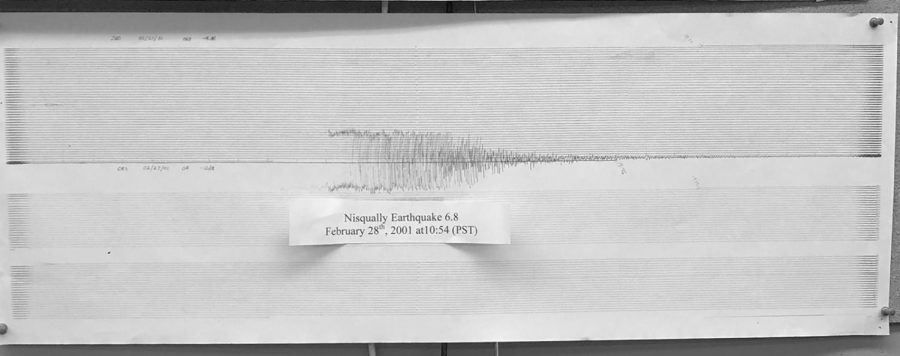

The immense friction between the two plates as they contact one another builds massive potential energy, which is occasionally released suddenly and violently. As a result, the plates, deformed by stress, abruptly reform, releasing that stress in the form of movement. This energy surges through the crest as an earthquake.

Due to the large size and length of the CSZ, the fault is expected to be capable of producing earthquakes up to a magnitude of 9.0 on the moment magnitude scale – roughly on par with the earthquake that devastated much of Japan in 2011, killing more than 15,000.

If a large earthquake occurs underwater, the movement of the crust could displace water, leading to a tsunami, a massive wave that can reach 100 feet high, inundating cities. According to the National Weather Service, it only takes six inches of moving water to sweep away a human, and two feet of water can carry away most vehicles.

These earthquakes occur on a roughly periodic basis, allowing seismologists to identify windows of several decades in which large earthquakes are more likely to occur.

For the CSZ, the last large earthquake occurred in 1700. Although no record of that earthquake exists, circumstantial evidence, such as trees found submerged that died in 1700 now thought to have been thrust underwater by the earthquake, layers of rocks buried along the coasts consistent with previous earthquake events, and an “orphan tsunami” that arrived without an earthquake off the coast of Japan in 1700 strongly suggest to seismologists that such an earthquake existed. Additionally, anthropological evidence suggests that the Pacific Northwest region has seismically active history. “There are a lot of native American legends that talk about it,” said Elizabeth Urban, a student at the University of Washington and a lab assistant at the Pacific Northwest Seismic Network, which monitors and studies seismic activity in the Cascadia region. “The Thunderbird and the Whale is the most common one in this area, where the earth is shaking, and there’s a storm, and there’s a tsunami.”

Large subduction earthquakes along the CSZ, Urban said, reoccur roughly every “300 to 500 years” from the previous large quake. This broad range of dates underlines a common misconception that Urban says is held about the Cascadia earthquake. “The biggest misconception is that we are overdue,” she said. “You might have heard that we are overdue for the big one. We can’t predict exactly when an earthquake will happen. We can talk about its recurrence intervals, because as much as the world is crazy and unpredictable, over a long enough scale, we can actually see trends.”

As the last large earthquake occurred in 1700, the next large earthquake is expected between the years 2000 and 2200. “So then you get to do some really concerning math in your head, and you think ‘Okay, the last one was in 1700, so that means it’s been 318 years’,” she said. “So we are in a recurrence interval right now. We’re gonna be in that for 200 years. So it could happen tomorrow; it could happen in 150 years, and you’d still be right.”

Although seismologists can roughly identify when earthquakes are more likely to occur based on past evidence, they cannot predict exactly when they will take place. “We are really hesitant to talk about unusual activity before large earthquakes, because we get into this complicated area of earthquake prediction, which some people are trying to pursue as a possibility, but generally, the scientific community accepts that it’s not something that we can really do. The earth is going to move when it is ready, and we can’t really predict that.”

Regardless of the uncertainty of time, communities in the Cascadia region are preparing. Many say that the city of Seattle, built partially on reclaimed land, is particularly vulnerable for an earthquake, as that land is susceptible to liquefaction: the process by which water in the soil rises to the surface, effectively turning once-solid ground into a lake.

On the coast, small, isolated communities are preparing for the worst. The small size and distance between these towns means that in the event of a large-scale disaster, they could be on their own for up to three weeks. “‘Worst-case scenario’ is a very tricky thing to say, because the worst-case scenario could be very bad if we’re going to take that word and run with it, but, generally, the most unsavory answer is that you could be on your own for up to three weeks, just because of the challenging layout of our state.”

Urban recalled a program called Cascadia Rising, where local emergency crews, in association with FEMA, simulated an earthquake and the aftermath. “And it went from a lot of the government estimates saying, ‘Be prepared for up to 72 hours, three days [of isolation],’ to up to more in the two-to-three weeks range just because of current capabilities.”

In the more closely-packed Seattle metropolitan area, of which Mountlake Terrace and surrounding communities are a part, isolation is not as much of a concern, although it still pays to be prepared. In case of an earthquake, emergency services and cellular communication may be disrupted, leading to some periods of seclusion. Fires may break out due to broken gas lines, there may be limited electricity, and some people may be injured. The school ideally prepared for an earthquake, according to Urban, has stockpiled basic supplies, such as food, water, and medical supplies, and trained its students and staff about proper procedure in case of an earthquake.

That procedure is a simple process known as “drop and hold”: when the shaking starts, drop to your hands and knees to avoid being knocked over, being sure to cover your head and neck; then, if one is nearby, crawl beneath a sturdy desk, table or chair, or, if not, next to an interior wall without windows, then remain there until shaking stops. “Be aware that that might not be the only shaking you feel,” Urban said. “Aftershocks are a thing as well, so if you feel [additional shaking], get back under and protect your head and your neck.”

According to the Great ShakeOut, a project of the South California Earthquake Center (SCEC) at the University of Southern California sponsored by FEMA and the USGS, earthquake injuries come from people being struck by objects thrown or knocked off of high places by the violent shaking. Hiding under sturdy cover helps mitigate that risk.

As cities and communities prepare for the eventuality of sudden, unannounced earthquakes, the UW, in collaboration with UC Berkeley, CalTech, the University of Oregon, and other government agencies and research institutions, have been working on a program known as ShakeAlert, which is an app designed to give communities a heads-up on earthquakes.

“It takes advantage of the speed of earthquake waves,” Urban said. “The initial wave isn’t the most destructive, and it travels faster than the more destructive wave, so our stations can detect this faster but less damaging wave and can send out an alert saying, ‘Okay, based on what we know about waves,’ it’s a very standard speed that these waves travel at, ‘we can say that a damaging shaking is going to reach you in five seconds, twenty seconds, up to three minutes depending on where its located.’”

By integrating an early warning system, Urban says, cities could have several crucial seconds to prepare. Although that may not sound like much, it is time enough that surgeons could stop delicate surgery, trains and trams could come to a stop, and people everywhere can drop and hold before the shaking begins.

While no building is earthquake-proof, and no emergency procedure is infallible, the work being done by seismologists at places like the PNSN will help us to be better-prepared for an earthquake. Until that time when we have a more complete understanding of seismology and can use that to effectively predict earthquakes, for now, we can only enjoy the beauty of the mountains created by plate tectonics.