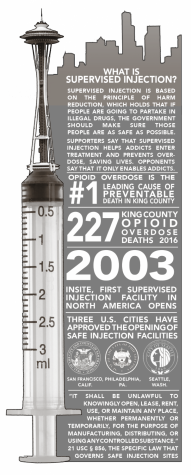

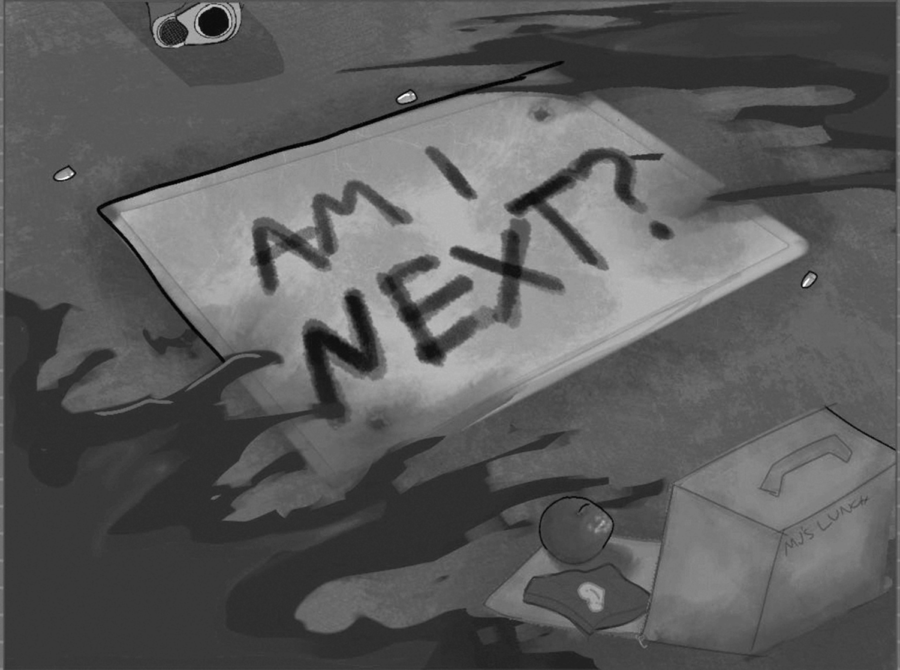

“The King County Medical Examiner’s (KCME) Office reported that deaths caused by drugs increased to their highest levels in 2016 in both Seattle and King County, Washington,” reads a June 2017 report on opioid abuse released by the Seattle Field Division of the Drug Enforcement Administration. “The majority (63 percent) of the 360 deaths were caused by opioids. The opioids responsible for the overdose deaths were opium derivatives such as morphine and heroin, but also included oxycodone, hydrocodone and methadone. In addition, synthetic opioids such as fentanyl, fentanyl-related compounds and U-47700 were also found.”

The report points to a conclusion that city, local and state leaders know all too well: the opioid epidemic in Seattle and Washington continues to grow out of control. A September 2017 report by KOMO found that Snohomish County had run out of kits with which to clean up discarded needles in just two days. The county had a supply of 50 such kits containing personal protective equipment, sharps containers and hand sanitizer to distribute so citizens could clean up any discarded needles they found, but found that more people needed them than anticipated. According to KOMO’s figures, opioid overdose ranks in King County as the

number one cause of preventable death.

The problem is one we’ve faced before, with Nixon’s War on Drugs and the crack epidemic in the 80s. This time, it’s back with a vengeance. The AP reports that even though fewer than 5,000 overdose deaths were recorded in “1988, around the height of the crack epidemic, more than 64,000 Americans died from drug overdoses” in 2016, citing the CDC. In the Seattle area, a graph by the DEA shows deaths from heroin increasing rapidly from less than 30 in 2009 to over 140 in 2013. Although opioid overdoses take place all up and down the Seattle isthmus, most take place in the city’s downtown.

Legislative solutions have already been emplaced. A 2017 bill passed that edited much of the existing legislation regarding opiates allowed healthcare providers greater oversight as to the prescription of opiates and expanded state authority to legislate opiate prescription. A bill introduced early in the 2018 session and currently in the House Committee on Healthcare and Wellness would limit the amount of opioids that could be prescribed at one time, from a three-day supply for those under 21 to a seven-day supply for those over 21 at practitioner’s discretion. The News Tribune of Tacoma reports that Governor Jay Inslee requested in January a bill to spend $2.3 million dollars a year to expand a state program that deals with addiction, housing, employment and social services.

Supervised injection in America?

One of the more obscure entries among the arsenal of weapons with which to combat drug abuse is the idea of the supervised injection site. The name is fairly self-explanatory – it is a safe and clean place in which addicts can, according to the New York Times, “shoot up under the supervision of medical staff ready to revive them if they overdose.” They are based on harm reduction: the principle that if illicit drug use is inevitable, the government should make it as safe as possible to partake in it. Many exist in Europe in countries like Germany and the Netherlands, and the first North American site opened in Vancouver, B.C. last year. Vancouver has since opened a second location, and supervised injection sites in Edmonton, Toronto, Montreal and Ottawa have since opened.

In the United States, however, none exist. But in the face of rising overdose numbers, they have gained new traction among large cities with drug problems. Seattle, San Francisco and Philadelphia have all approved the opening of supervised injection sites, and a bill that would allow the establishment of a supervised injection site in Colorado was shot down in the legislature in February. San Francisco is poised to be the first to open a supervised injection site, with doors slated to be opening in July, and Seattle has allocated $1.3 million dollars for establishment and operation of a supervised injection site – which would be called a CHEL, for Community Health Engagement Location – in its 2018 budget. The City Council is currently discussing the placement of such a site in the city. Plans by the city to open a second site outside of Seattle are currently on hold until the first one is opened.

Saving lives?

Proponents of supervised injection sites mainly focus on the reduction in infectious disease and overdose deaths that supervised injection sites are thought to bring. The New York Times said in a February editorial that although “it may seem counterintuitive [to] give drug users space and support to inject themselves with potentially deadly substances, even while encouraging them to stop,” supervised injection sites remain an “important, rigorously-tested harm reduction method.” They cite “dozens of studies” that point to the conclusion by that supervised injection sites reduce overdose deaths and increase the number of people in treatment. “Despite millions of objections that have occurred at more than 90 facilities internationally over the past three decades,” they say, “not a single overdose death has been recorded.”

Mark Lysyshyn, Medical Health Officer for Vancouver Coastal health claims that the presence of a supervised injection site “definitely prevents overdose” and encourages addicts to enter into treatment. He also claims that supervised injection sites benefit “‘community order’”, saying that “there has been less crime in the area, less needles, less injection. We had a real epidemic of HIV among the drug-using community in the area and those rates have really plummeted.”

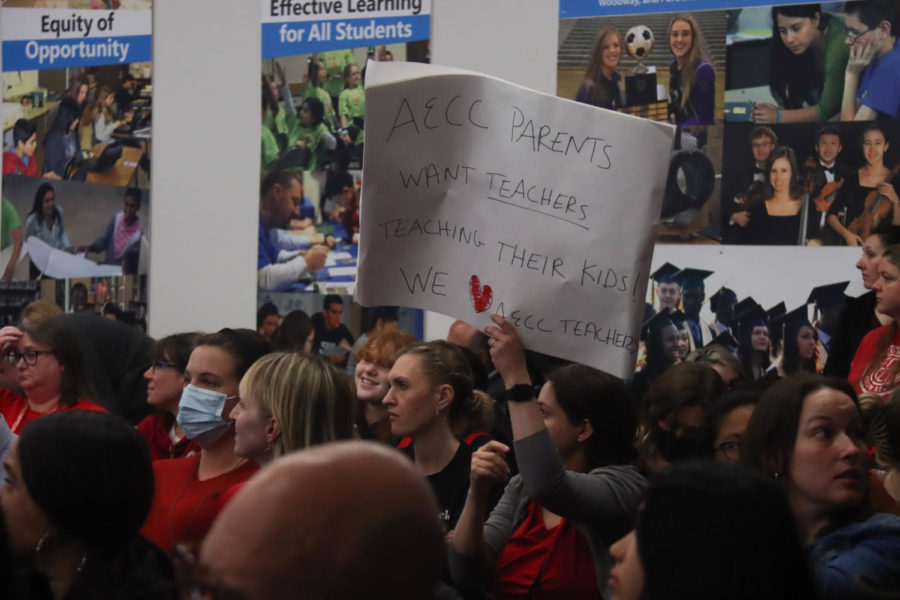

Relatives of many addicts support the measure. “My beloved daughter Marah, aged 19, died in my home from a heroin overdose,” said local TV personality Penny LeGate, former co-host of King 5’s Evening Magazine and former morning anchor for Kiro 7. “I agonized so much over the what-ifs. What if there had been a safe consumption site? Where is the urgency?”

Enabling addicts?

However, the benefits are not always readily apparent. “When [Vancouver’s supervised injection site] was first established, we allocated significant resources to the area and it’s typically been an area where there’s a tremendous amount of injection drug use, said Tom Stamatkis, president of the Vancouver Police Union. “Why are we creating supervised injection sites but essentially saying to the addicts, ‘You have to find your own way to buy the drugs’ – so they’re committing crimes?”

Jamie Graham, Chief of the Vancouver Police when the site opened, claims that “the focus of harm reduction is the worst-case scenario for a drug user — total inability to quit and eventual death.” The best solution, Graham says, is “support, treatment, abstinence and counseling.”

Perhaps the most common argument against supervised injection sites is that they enable addicts. “I’m not a fan,” said former Washington Attorney General Rob McKenna on KIRO radio, “because I think there’s no getting around the fact that safe injection sites, sort of, normalize heroin addiction. They socialize it as something that we don’t really like, but it’s something we will, in a sense, sanction.”

Supervised injection sites continue to gain traction in many of America’s cities. In addition to the three cities that have already approved their establishment, city officials in Ithaca and New York, among others, are considering starting their own programs.

At the same time, however, many cities continue to shy away from the supervised injection concept. Supervised injection has been banned in Bellevue, Renton, Federal Way, Auburn and unincorporated Snohomish County, and a measure to ban them in King County was slated to appear on the February 2018 special election ballot until it was removed by a judge for infringing on the authority of the King County Board of Health.

Federal resistance

Supervised injection is also meeting resistance at the federal level. In response to a proposed site in Vermont, the US Attorney’s Office for the District of Vermont called supervised injection sites “counterproductive and dangerous,” and claimed that they “normalize heroin use, thereby increasing demand for opiates and, by extension, risk of overdose and overdose deaths” and “violate several federal criminal laws, including those prohibiting use of narcotics and maintaining a premises for the purpose of narcotic use.” A DEA spokesperson, Kathleen Pfaff told BuzzFeed news that “so-called safe injection sites violate federal law” and that “any facilitation of illicit drug use is considered in violation of the Controlled Substances Act and, therefore, subject to legal action.” The Trump Administration’s hard-on-drugs approach that Trump promises to be “really, really tough, really mean with the drug pushers” could signal a legal challenge to the prospect of supervised injection sites. Specifically, the law that both the Vermont District Attorney’s office and Pfaff cited is a 1986 statute designed to deter people from profiteering off of crack dens. Known as the “crack house statute,” 21 USC § 856, it makes it illegal to “knowingly open, lease, rent, use, or maintain any place, whether permanently or temporarily, for the purpose of manufacturing, distributing, or using any controlled substance.”

But, King County Prosecutor Dan Satterberg says, it’s a challenge that the county is willing to take. “I am just girding for the legal battle,” Satterberg told BuzzFeed, “and that could be a lot of fun — a face-off with Jeff Sessions.” According to Satterberg, supervised injection sites and crack dens are polar opposites. Due to the difference in purpose and the positive impact they make on communities, he says, the crack house statute does not apply. “This administration doesn’t have much regard for science, but there have been extensive studies on the 90 safe consumption sites already working in Europe, and Canada, and all over the world,” he told KIRO Radio. “And it’s proven to be an effective place; for that connection to be made between a medical professional and a drug user who may want help. The evidence is there, they are choosing not to look at it. And they are using it for political purposes.”

As of right now, no tangible legal challenge at the federal level has manifested itself. At the state level, Governor Inslee told KIRO that the decision to establish or ban supervised injection sites will be left to the communities. Due to the complicated nature of the issue, it is unlikely that a lasting decision will be made on supervised injection in America, but until then, the concept of supervised injection continues to slowly move forward in Seattle.