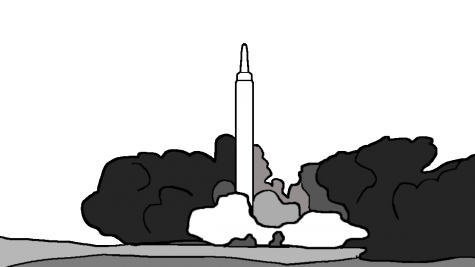

A puff of smoke. A flash of light. A long, deep, menacing hiss and the long, slender missile lifts from its launch pad in Pyongsong, North Korea, just 18 miles from the capital of Pyongyang. A dark tube interrupted by a white checkerboard pattern, the Hwasong-15 intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) flew for 53 minutes, reaching a maximum altitude of 2,780 miles and landing 590 miles from its launch site in the Sea of Japan, according to figures released by North Korea’s state-run media agency.

The test of the Hwasong-15 ICBM is, as of writing, the latest in a series of missile tests that have drawn increased public attention in recent years as North Korea has ramped up its nuclear program.

The North Korean nuclear program detonated its first atomic weapon in October 2006, to much consternation from Western nations. The Washington Post reports the second Bush administration (prematurely) estimated in the early 2000s that the North had developed or was close to developing an ICBM with the range to strike the US mainland. Jeffrey Lewis, director of the East Asia Nonproliferation Program at the Center for Nonproliferation Studies, has said that the North decided to skip the development of the simpler implosion-type weapon that the United States dropped on Imperial Japan in 1945.

“So, while the world was laughing at North Korea’s first few nuclear tests,” Lewis said in Foreign Policy magazine, “They were learning — a lot.”

But why should the students of MTHS care?

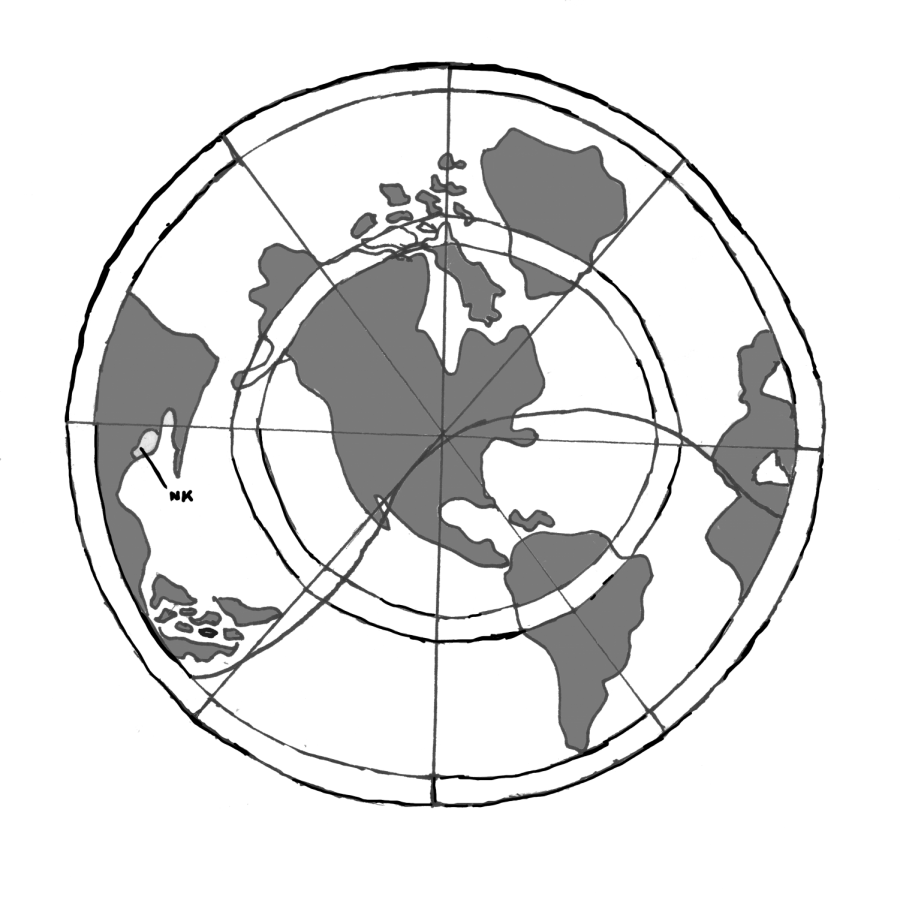

As it turns out, there is a big reason. The flight characteristics of the Hwasong-15 missile have led experts like David Wright, co-director of the Union of Concerned Scientists, to believe that, with a light payload, the missile could possibly reach Washington—both the capital and the state. According to 38 North, a Korea-focused blog run by the School for Advanced International Studies at John Hopkins University, while a 600 kilogram payload would be able to reach Seattle, to reach the “western edges” of the mainland US, a 350 kilogram payload is required (how Seattle differed from the “western edges” of the mainland was not specified).

It’s important to note the distinction between having the capability to launch a missile and the capability to use that missile to launch a nuclear weapon. A nuclear-tipped ICBM carries one or more miniaturized warheads, or nuclear weapons that have been compacted enough to be carried atop a nuclear warhead. Miniaturization is an important milestone on the road to becoming a full-fledged nuclear power.

The problem is, it appears North Korea has already done that. The Washington Post reported in August, the month before North Korea conducted its sixth nuclear test, that US intelligence officials had determined North Korea had successfully miniaturized a nuclear warhead.

“[North Korea has] done five nuclear tests now,” NPR science editor Geoff Brumfiel said on All Things Considered. “And other countries have been able to miniaturize in fewer tests. So it seems reasonable to assume that they might have been able to miniaturize by this point.”

But what is North Korea’s goal in having nuclear weapons?

Getting a clear answer from a nebulous country effectively sealed from the Western world is difficult. Many assessments say that one of North Korea’s main intentions is to gain international credibility as a regional player and a nuclear power. Forbes contributor Ralph Jennings says that North Korea “is probably not preparing for a war, just its own style of deterrence,” and that “The tests remind other countries to leave it alone, rebut foreign criticism of Kim’s regime and may be used someday as a bargaining chip.” The New York Times cited Cameron Munter, former US Ambassador to Pakistan and director of the EastWest institute, in saying that “There is a certain universality of wanting to be recognized and respected, and because Americans take this for granted, they don’t see just how deeply motivating that search for respect can be.”

Another school of thought goes beyond simple deterrence and recognition and surmises that North Korean leader Kim Jong-Un aims to force the United States to, according to Max Fisher of the New York Times, “[conclude that North Korea] has grown too powerful to coerce and the status quo too risky to maintain, leading Washington to accept a grand bargain in which it would drop sanctions and withdraw some or all of its forces from South Korea.”. A report by the BBC says North Korea’s posturing stems from “a rational assessment of the country’s strategic interests”, centered around the perceived “clear threat” significant American military presence on the Korean peninsula, and that “the North’s nuclear aspirations date from the 1960s and are consistent with the regime’s desire for political and military autonomy in the face of opposition not only from its traditional enemies such as the United States, Japan and South Korea, but also over the objections of its historical partners such as China and Russia.”

Perhaps the most frightening thought is that North Korea intends to reunify the Korean Peninsula – by force. B.R. Myers, associate professor of international studies at Dongseo University in Busan, South Korea, said in the L.A. Times that “North Korea is a radical nationalist state and it’s committed to anything that anybody in North Korea’s position would be — which is the reunification of the [Korean] race, and the reunification of the homeland.” Myers questioned why the North would seem to be pushing the U.S. towards launching a strike of any sort, noting ominously that “the only logical answer is that it’s pursuing something greater than mere security — and there’s only one logical conclusion as to what that is.” Yun Sun, associate at the Stimson Center, a Washington, D.C.-based think tank, said that North Korea’s aim is to use nuclear weaponry as a threat to deter the United States from intervention in case of a reunification campaign.

But is war really coming?

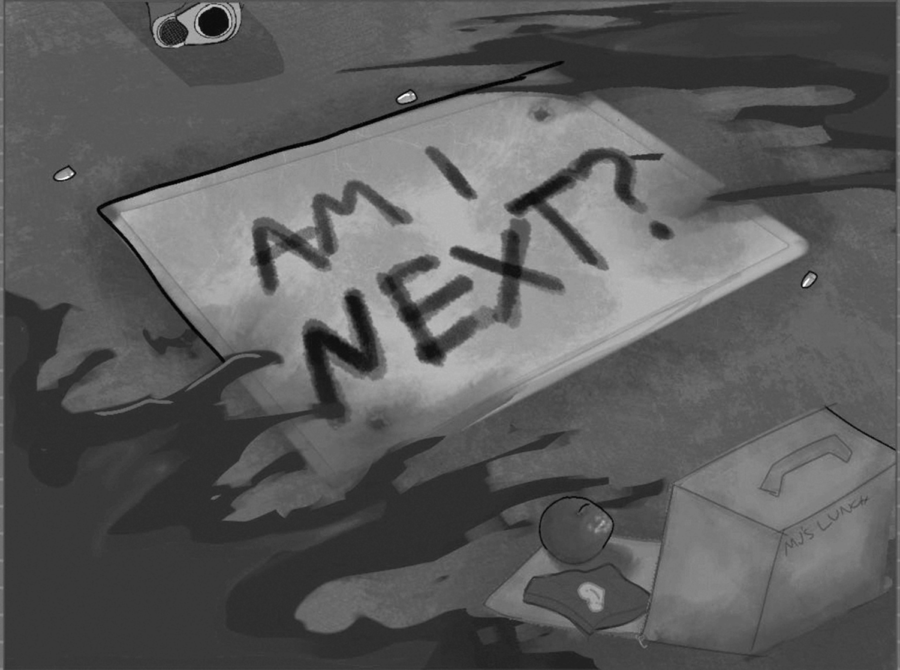

It’s difficult to tell, but the relations between the U.S. and North Korea are definitely tense. Admiral Michael Mullen, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff under Presidents Bush and Obama, told ABC’s “This Week” on New Years’ Eve that the US and North Korea are “closer to a nuclear war” than ever before. In 2013, North Korea withdrew from the armistice that de facto ended the Korean War, formally reopening the 1950 conflict that technically never ended. The United States continues to conduct routine war games, shows of force and readiness exercises around the Korean peninsula in conjunction with South Korea, which the North frequently denounces as rehearsals for war. A cell phone alert sent out erroneously January 13 by the Hawaii Emergency Management Agency warning in all-caps of a “ballistic missile threat inbound to Hawaii” plunged the state into a panic and illustrated the fear that hangs over much of the Pacific. Just three days after that, the Japanese public broadcaster, NHK, sent a similar alert, warning of a North Korean missile, to Japanese citizens. Both alerts were the result of human error, and while the Japanese alert was retracted within five minutes, it took 38 for the Hawaiian alert to be retracted as HIEMA had no procedure or protocol for a false alarm.

This message was inadvertently sent to residents of Hawaii on Jan 13.

Communication between the US and North Korea continues to be acidic and polemic, with North Korea calling America a “graveyard of human rights” and a “gangster” country in the throes of “nuclear war mania” whose leader, President Trump, is a “lunatic old man” and a “mentally deranged U.S. dotard”. In response, President Trump, in a speech to the UN, referred to Kim Jong-Un as “Rocket Man” and said he was on “a suicide mission for himself and his regime” and threatened to “totally destroy North Korea” if provoked. On Twitter, President Trump called “Little Rocket Man” a “sick puppy”, and in a later tweet, called him “short and fat”. North Korea has denounced UN sanctions as an “act of war”, and the November redesignation by the US of North Korea as a state sponsor of terrorism as a “serious provocation”. In his New Years’ Day speech, Kim said that “The entire mainland of the US is within the range of our nuclear weapons and the nuclear button is always on the desk of my office. They should be aware that this is not a threat, but a reality.”

Despite this, however, there are still some peaceful tones in the messages between North Korea, South Korea and the United States. In the same New Years’ Day speech in which he reminded the US of his newfound nuclear capability, Kim offered to send a delegation from North Korea to the Winter Olympics in Pyeongchang, South Korea in February; to prepare for negotiations, the two countries reopened on January 3 a telephone hotline at the border that had been closed in February of 2016 by the North. At negotiations held Tuesday, January 8 at the border town of Panmunjom, North Korean negotiators agreed to send a delegation of athletes and other staff 550 strong the Olympics. During the opening ceremonies, the Olympic teams of the two Koreas will march together under the flag of a unified Korean peninsula. The North will also send a 140-member orchestra called the Samjiyon Band, called “one of the North’s top arts troupes” by the New York Times, to play twice in South Korea. The South Korean delegation also proposed at Panmunjom the re-opening of a program that allowed elderly Koreans on either side to temporarily reunite with family across the border. President Moon suggested in December that the United States postpone the scheduled yearly training exercise known as Foal Eagle. In November, during a speech to the South Korean National Assembly, President Trump, while warning the North not to test American resolve and denouncing what he called a “prison state”, offered a “path to a better future” and stated his desire for “North Korea to come to the table and make a deal that is good for the people of North Korea and for the world.”

Although the exact state of their nuclear capabilities remains uncertain, North Korea is a dangerous country that should not be underestimated. A conventional war would cost hundreds of thousands of lives, according to the Congressional Research Office, and a war that escalates beyond that might cost millions — or more. Regardless of whether or not tensions continue to increase, the North Korean issue is one that should be watched carefully as, as Obama administration officials warned incoming Trump administration officials before his inauguration, one of the most important issues currently facing America.