In 2009, the personnel director for the Chicacum School District walked into a courtroom of the King County Superior Court to be cross-examined in a case about education funding. Afterwards, Stephanie McCleary and her children, nerves frayed from hours of questions from state lawyers, went to look at puppies.

At the time, nobody — not her, not her son Carter, not King County Superior Court Judge John Erlick and especially not the puppies — could have known how big the case bearing her name would grow.

Today, the case known as Matthew and Stephanie McCleary et al., v. State of Washington remains one of the hottest issues on the legislative platter. In short, the case holds that, as determined by the state Supreme Court, the State of Washington does not and has not fulfilled the duty defined by the Constitution as its “paramount duty”: the “ample provision of education of all children residing within its borders.”

The case, which was filed in 2007 by the Network for Excellence in Washington Schools (NEWS) on the McClearys’ behalf and in their name, is still being argued today. But how has the case progressed since the initial decision against the state in 2010?

On paper, the state has made much progress. In 2012, the state was ordered to raise its education spending to levels that would amply provision education by 2018, and was also ordered to publish progress reports following its yearly legislative sessions. In 2014, the state was held in contempt for not making adequate progress towards finding a budgetary solution. And in 2015, the court ordered the state to pay $100,000 for every day that it fails to submit a budgetary plan that would fulfill the court’s requirements.

However, even as the legislature continued to debate legislative proposals and pass budgets, a solution that the state argued would once and for all fulfill its obligations under McCleary remained elusive.

Until this month.

Engrossed House Bill 2242 (EHB2242) was first read by legislators June 29 of this year, and by the next day, it had been read twice more and submitted to Governor Inslee, who passed it with the exception of four sections of the bill, which were deemed to be going “against the intent of this bill.”

According to the state, EHB2242 is the solution to the McCleary problem. In a document entitled State of Washington’s Reply and Answer to Amici Briefs, originally filed Sept. 8, 2017 and updated Oct. 12, the state argues that it has “achieved compliance with article IX, section 1 of the Washington Constitution by implementing and fully funding the education reforms that this Court endorsed in 2012.”

The document says funding for K-12 education nearly doubled from $13.4 billion in the 2011-13 period to $26.6 billion in the 2019-21 period.

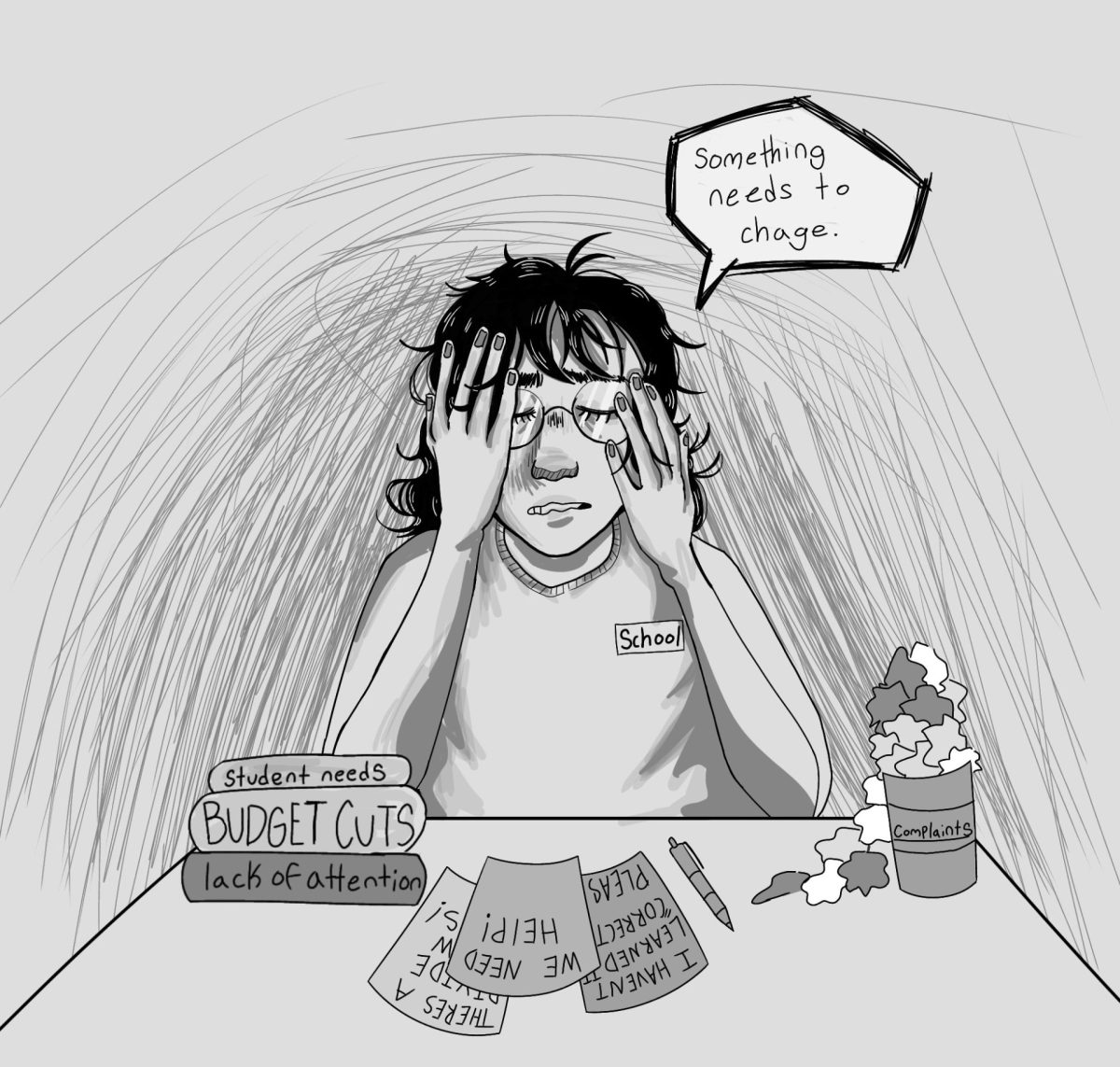

But does this bill really do all that it is purported to? Does it fulfill the state’s obligations to students, teachers and districts?

“The short answer would be no,” said Dr. Kristine McDuffy, superintendent of the Edmonds School District. “There has certainly been progress made, but we have a lot of gaps yet to fill.” These gaps include lapses in funding for special education and teachers’ salaries.

“[With regard to salary funding], it was a step,” said McDuffy. “We are still trying to understand what the new funding model is going to look like. The state will be issuing some examples of a state salary schedule, we believe, in the next couple months, but we haven’t had a chance to see that yet, so we’ll have to stay tuned.”

That theme — that the bill is too new, meaning significant study into its effects and debate on its provisions has yet to happen — seems to be a prevalent one. Although the state says the bill fulfills its McCleary requirements, the arguments before the state Supreme Court about whether or not it actually does so are not scheduled to happen until October 24th, which is over a week after the time of writing.

McDuffy’s sentiment that the bill is not comprehensive enough is one that is not just harbored by her. An August editorial by the Seattle Times said that the legislature’s work was “far from finished”, with another editorial a month later with “done” in place of “finished” from the Everett Herald.

“Yes, this feels like a step forward, but there are a lot of unknowns,” said MTHS interim principal Greg Schellenberg. “There’s further legislation to come, and once that starts being decided and communicated then the districts will know how to respond. It’s not clear. So, do I feel like it’s satisfied the obligation? Not right now, because it feels like it’s not done.”

In years past before EHB2242, school districts were funded largely thanks to temporary increases in local property taxes, known as levies. Exactly how much funding a school district gets depends largely on the value of local properties.

According to the majority opinion of the state Supreme Court in 2012, which held that the state was not fulfilling its “paramount duty” of education, “Districts with high property values are able to raise more levy dollars than districts with low property values, thus affecting the equity of a statewide system.”

Conversely, they said, a district whose property was not as valuable would not be able to fund an education compliant with the state constitution.

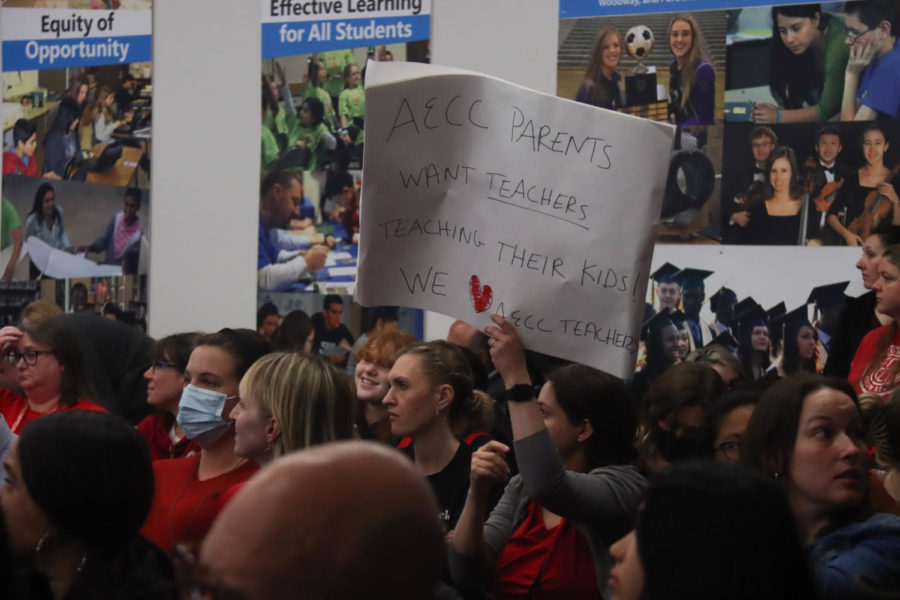

The receptiveness of citizens to being taxed is also an important factor.

“You’ll have some pockets of the state that are going to be passing levies for great amounts and you’ll have other pockets that will struggle to pass levies for any amount. The amount of education and access that that turns around for the students is quite different,” said Schellenberg.

Exactly how much money will be funnelled into ESD is a number encrypted deep within the legalistic passages of the 121-page document known as EHB2242.

“We are still trying to understand what the impacts are going to be because our local levy is going to be reduced by a significant amount, so there’s the rest of the story,” said McDuffy.

McDuffy referred to a new stipulation in the bill that limited the amount that districts can raise to either $1.50 for every $1,000 in property in the county or $2,500 per student, whichever is less.

“The state is going to be flowing through additional revenue but our local levy collections are going to be dramatically reduced, and we are still trying to wait and see what the net effect is going to be,” McDuffy said, “so it is not simply looking at [any additional revenue that EHB2242 claims will be added to ESD]. We believe we’ll see some additional, but we’ve got some huge gaps to fill.”

These gaps come most visibly in the form of increased class sizes. Many classes are at or above their contractual limit of 31 students allowed before something called “trigger funding” kicks in, which gives teachers additional funding to deal with more students. Less visible are decreased funding for special education, English as a Second Language, counseling and other similar programs.

Again, the precise amount of additional money that will be given to these programs as a result of McCleary and EHB2242 is unknown.

“I don’t think it’s impacted students’ experience as terribly [as it could have], but behind the scenes it’s been a matter of who’s paying the bills, and then it trickles down to students and their families supporting it rather than the state supporting it automatically,” Schellenberg said.

The problem of “who’s paying the bills” is the most important one here. As the Supreme Court said, property value imbalances affect the ability of districts across the state to educate their students equally.

Although the state claims that its work is done, arguments on behalf of both the state and NEWS have, at time of writing, not even begun.

(Those arguments, regarding whether EHB2242 fulfills the state’s McCleary obligations, are slated to begin Tuesday, Oct. 24.)

The Seattle Times said in its August editorial that such a definitive conclusion on the McCleary issue should not be made until “school officials have time to fully analyze the new system the Legislature passed in a whirlwind more than a month ago” — a process, they said, that could take up to a year.

Despite the fact that a complete assessment has yet to be made, so far, the outlook is not a positive one.

Spokane school officials estimate that even with added state funds, the special education budget will still be $2-4 million short. Seattle school officials estimate a gap of over $50 million. Here at home, it’s a similar story.

“[The added funds are] not going to get to the place that the Supreme Court has determined is the definition of basic education for our district and every district across the state. There’s a shortfall for sure,” McDuffy said. “We’re just trying to determine what the real gap is, and that’s where the Supreme Court is going to hear arguments from both sides of the lawsuit on Tuesday [Oct. 24].”

Today, Carter McCleary has graduated — he was a senior when he wrote a special for the Times in January of this year. But the trial filed in the name of him, his sister Kelsey, his mother Stephanie and his father Matthew (whose name was spelled incorrectly in the case paperwork), still roils about in the Temple of Justice in Olympia.

As different opinions about EHB2242 continue to swirl about the capitol and the community, it is still, for now, undecided whether the state has finally fulfilled its paramount duty — the education of the students of Washington, Edmonds School District and MTHS.