The Pledge of Allegiance, familiar to most involved in the American education system, has created much controversy over the course of its nearly 125-year long existence. The official text of the pledge has been changed four times since its creation and there have been four different Supreme Court rulings issued regarding the famous Pledge of Allegiance.

The original version of the Pledge of Allegiance was created by Baptist minister and Christian socialism activist Francis Bellamy. Bellamy wrote the Pledge as a way to promote American patriotism among schoolchildren, especially the children of immigrants. He published the first version of the Pledge in 1892, in honor of the four hundredth anniversary of Christopher Columbus’ arrival in the Americas.

Bellamy originally considered adding the phrase “with liberty, justice, equality and fraternity for all” to the end of the Pledge, but ultimately decided to remove the words “equality” and “fraternity” due to his belief that the state boards of education would reject those words, as they did not see equality for women and African Americans as ideal.

Bellamy’s original version of the Pledge read, “I pledge allegiance to my flag and the Republic for which it stands, one nation indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.” In 1923, fearing that immigrant children would think they were pledging allegiance to the flag of their birth country instead of to the flag of the United States, the words “my flag” was changed to “the Flag of the United States of America.” The word “flag” was later capitalized for emphasis.

The state law and school district policy regarding the Pledge of Allegiance, which have been shaped by the decisions of the Supreme Court, state that time should be set aside for the recital of the Pledge of Allegiance each school day. However, students cannot, by federal law, be compelled by the staff to recite the Pledge due to the constitutional rights of freedom of speech and expression guaranteed by the First Amendment. Principal Greg Schwab sends out an email to MTHS staff every two years reminding them of these requirements.

“It’s one of those things that every couple of years we should remind everyone about,” Schwab said about the district policy on the Pledge. “The policies regarding the Pledge are not widely known and everyone should be reminded of them every couple of years so that we can be sure that they are being followed.”

In the 1943 West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette ruling, the Supreme Court ruled that a student could not be required to stand for the Pledge because the requirement violated the First Amendment. This overrode the Minersville School District v. Gobitis decision from 1940, which said students could be required to stand for the Pledge. However, many schools and communities still maintained an expectation that students stand for the Pledge, viewing it as an essential part of American patriotism. Though its recital cannot be legally required, many still view the Pledge as a social and cultural necessity.

This expectation has remained prevalent in American society for many decades and Schwab believes it can still be present in classrooms today.

“A lot of us have a lot of personal beliefs [about the Pledge], especially those of us who are of the older generation and were required to stand for the Pledge and grew up in a different time with different expectations,” Schwab said. “I think that sometimes those values can creep into the current day and we just have to be mindful of what the law actually says.”

This clash of generations regarding the Pledge is something found throughout the country. In 2006, a school district in Florida was ordered to pay $32,500 by a district court to a student who refused to recite the Pledge and was ridiculed and called unpatriotic by their teacher. Prior to this ruling, a law in Florida required students to stand for the recital of the Pledge.

Though students are not obligated to recite or stand for the Pledge of Allegiance, district policy and state law are clear in requiring that students who choose to sit during the recital of Pledge “maintain a respectful silence.” During the Pledge, all students are required to not talk, play music or participate in any other activity that would disrupt the rights of other students who choose to recite the Pledge.

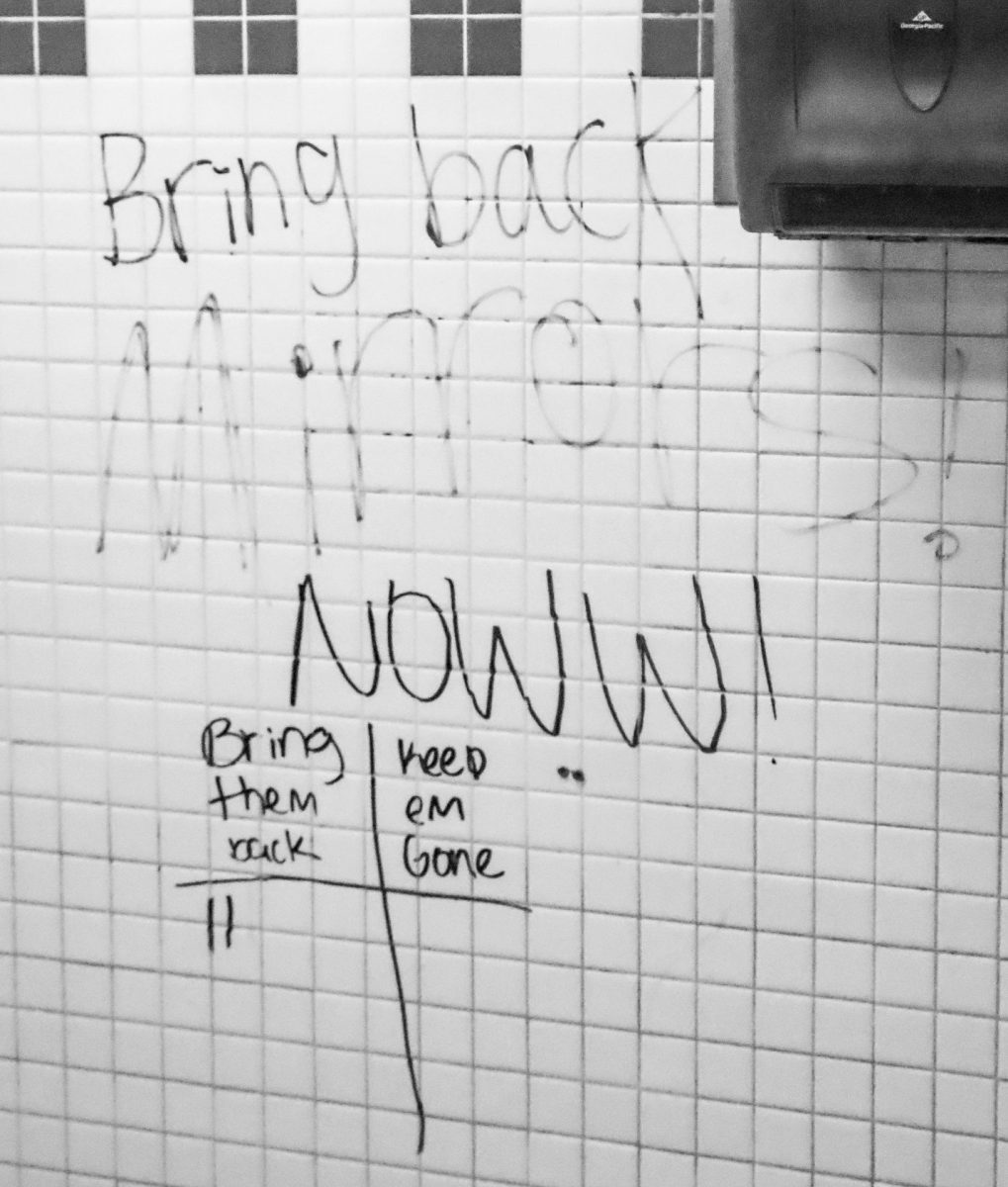

At MTHS and statewide, many students choose not to participate in the recital of the Pledge of Allegiance. Their reasons for nonparticipation range from religious reasons, which prevent perceived idolatry, or the worship of people and objects other than God, to the belief that people should not have to pledge their allegiance to the flag of a free nation.

Sophomore Reiden Chea is one student who chooses to not stand for the recital of the Pledge due to America’s current political status.

“I choose not to stand for the Pledge of Allegiance because I believe that the values of liberty and justice for all shown, in the Pledge of Allegiance, do not apply to our country anymore since people can be kicked out of our country just because they are immigrants,” Chea said.

Additionally, many students choose to omit the words “under God” when they recite the pledge. They view this part of the Pledge as unconstitutional as they see it as violating the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment.

The Establishment Clause is the first section of the First Amendment, which states “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” Many believe the phrase “under God” in the Pledge constitutes a government endorsement of monotheistic religions, thus violating the Establishment Clause.

The American Humanist Association requests that its members sit during the recital of the Pledge until the “under God” portion is removed.

Freshman Amy Harris has another approach. She chooses to skip over the phrase “under God” while reciting the Pledge of Allegiance.

“America is not an exclusively Christian nation and I do not believe that the phrase belongs in the Pledge of Allegiance in a society where the separation of church and state is meant to be valued,” Harris said.

The “under God” portion of the Pledge was added to the Pledge by Congress in 1954 at the request of President Dwight Eisenhower. This was during the height of the Second Red Scare when many feared potential communist influence on American society. Lawmakers at the time wished to emphasize the difference between the predominantly religious society of the United States and the officially atheistic Soviet Union. The daughter of Francis Bellamy objected to the change.

Since its addition, there have been many legal challenges to the phrase “under God,” with the most recent upholding of the phrase by a federal court coming from a 2010 decision from the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. In a 2-1 decision, the court stated that the words were merely “ceremonial and patriotic” and as such did not constitute the establishment of a religion.

Though the Supreme Court heard a case regarding the “under God” portion of the Pledge in 2004, during the Elk Grove Unified School District v. Newdow case, the case was ultimately thrown out due to the fact that Michael Newdow, the plaintiff in the case, was not the legal guardian of his daughter who attended school in the Elk Grove Unified School District. The Supreme court made no ruling regarding whether the recital of the “under God” portion of the Pledge was unconstitutional in a state-sponsored education.

Schwab believes it is important students are given the opportunity to express their opinions regarding the Pledge due to their rights which are guaranteed in the First Amendment.

“The opportunity to execute our First Amendment rights is central to being a citizen of our country. You cannot infringe upon a person’s right to exercise their free speech so long as it is not disruptive, advocates any illegal activities or is slanderous,” Schwab said. “Like it or not, we are founded on the First Amendment and that means you can say what you think and feel, or choose not to say what you think and feel.”

Schwab also wanted to make sure that people do not think students who choose to sit during the Pledge are any more or less patriotic than those who choose to stand.

“Just because someone chooses not to participate [in the pledge] does not mean that they have any less respect for our values or our country and what it stands for. In fact, it often times sends the opposite message, that they do value what our country stands for because they exercise their right to free speech by choosing not to participate,” Schwab said.

As well as mandating time for the Pledge of Allegiance during the school day, state law and district policy also require time for flag exercises at the opening of all school assemblies and immediately preceding interschool events, such as sports games, when it is considered feasible to perform them.

Flag exercises refer to either the recital of the Pledge of Allegiance or the performance of the Star Spangled Banner.

“When choosing between the two, it often comes down to if we have someone available to perform the national anthem. Sometimes at sporting events when we do not have the band available to play the national anthem, we do the Pledge of Allegiance,” Schwab said.

The same rules that apply to the recital of the Pledge of Allegiance also apply to the performance of the Star Spangled Banner. Students can choose to stand or sit and both actions are fully supported by state law, though everyone must maintain a respectful silence during the performance.

Regarding the display of the American flag in school, both state law and district policy require the flag to be displayed on or near all flag plants at all times, except during inclement weather. If an all-weather flag is possessed, it may be displayed at all times, even when the weather would not usually permit its display. These policies require that a flag must be displayed outside of every school and inside of each classroom. All government buildings are subject to similar rules and must have a flag displayed on or near them each day.

There is currently no federal law dictating when the Pledge of Allegiance should be performed in the school setting. That requirement is determined solely by the state legislatures and school districts.

The only Federal Law regarding the Pledge states what words are contained in the Pledge and the proper behavior for citizens who choose to recite the Pledge. This includes that non-military citizens should remove all non-religious headwear, place their right hand over their heart and face the flag. Members of the military should give a salute and face the flag. These rules also apply to during the performance of the Star Spangled Banner. The first time these requirements for the Pledge of Allegiance appeared in federal law was on June 22, 1942, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the first federal Flag Code.

All states, with the exceptions of Hawaii, Vt. and Wyo., specify in their state laws that time should be set aside in the school day for a recital of the Pledge of Allegiance.

Additionally, 17 states have also adopted pledges to their state flags and specify that these pledges should be recited immediately following the recital of the Pledge of Allegiance to the American flag. The first of these state pledges was adopted by Texas in 1933, which was soon followed by Georgia in 1935.

The states of Ky., Texas, La. and Miss. have a reference to God in the pledges to their state flags, while the states of Tenn. and Ala. have residents pledge their “service and life” to the state.