And with a final concurrence from Chief Justice Barbara A. Madsen, Washington state was found guilty in the famous Washington state Supreme Court case McCleary v. State.

The lawsuit was filed in 2007 by the Network for Excellence in Washington State (NEWS), a statewide coalition that campaigns for “ample funding” for all Washington students, according to their website.

NEWS filed the lawsuit on behalf of the McClearys and the Venemas, two families with students in the Chimacum School District in Chimacum, Wash. The McCleary and Venema children were young when the case began, when they first sat in the Washington State Superior Court.

Now, as the case has plodded along, Carter McCleary, who was 7-years-old when the case began, is a senior in high school.

In 2012, the Washington State Supreme Court ruled unanimously that Washington State was not meeting its “paramount duty” to provide “ample provision for the education of all children,” as stated in the case and Article 1 Section 9 of the Washington State Constitution respectively.

The plaintiffs won at “virtually every stage,” as NEWS Community Relations manager Teresa Moore stated.

The Supreme Court also defined keywords, such as “paramount,” “ample,” “all” and “education” in this stage.

Moore said the Supreme Court did something unusual and upheld and retained the jurisdiction, watching over the state and ensuring efforts were made to fund public education.

However, in September of 2014, the Supreme Court held the State in contempt for failing to make significant progress.

The Supreme Court documents stated that they had “repeatedly ordered the State to provide its plan to fully comply” with the court order by the 2018 deadline. The document continued, explaining that Washington State “repeatedly failed to do so.”

The Court filed for contempt and decided Washington state “must take immediate action to enforce its orders.” On Jan 9, 2014, the Washington Supreme Court imposed a $100,000 per day penalty on the State for each day it remains in violation of the court order. The money fined is set to go toward Washington state education funding.

The official deadline for the plan, as set by the Supreme Court, is the 2017–2018 school year, beginning in September.

State Senator Maralyn Chase said that the state legislature is “not even close” to devising a plan. She said the legislature will most likely have to hold special legislative sessions that go through the summer and into September.

“I don’t want to be here [at work] until September; I don’t think anyone else does either,” she said.

Originally, about seven months ago, a McCleary task force was created, with representatives from each Washington state caucus set to come up with a consensus plan.

Unfortunately, Palumbo said, the task force failed due to miscommunication and now there are two different plans, as set by the Democrats and Republicans of Washington state.

Republicans at first did not lay out a plan, Palumbo said, and instead the Democrats had their own plan that was not agreed upon by the other party.

As time went on, the Republicans created their own plan that was “short-notice” as defined by Palumbo.

He said that the Democrats’ plan is based off the existing system, regarding incoming revenue and the education budget, while the Republicans plan is more “radical” and “turns education on its head.”

There are two major possibilities, Chase explained.

Either the legislature can raise taxes among the citizens or they can take the funding from elsewhere, the “safety nets,” as she called them.

Chase explained that the problem that lies within finding a way to fund publication is the tax system. It’s the “only lense from which you can understand [the] McCleary [case].” Washington state has the number one “most regressive state and local tax system,” according to the the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP).

ITEP outlines how Washington state divides their taxes among the different economic classes, taxing the “lowest 20 percent,” those making less than $21,000 a year approximately 16.8 percent of their annual income.

The top 1 percent, those making above $507,000 a year are taxed approximately 2.4 percent of their annual income.

Chase said that, first, Washington state has to adjust their tax system to one that’s more “fair” and taxes each household equally. Afterward, the state must raise taxes.

According to Chase, taxes can’t be raised beforehand due to the bottom income households being “maxed out.” They wouldn’t be able to afford any more taxes, Chase said.

The one thing that’s not possible, in Chase’s own opinion, would be taking from the safety nets.

She, along with State Representative Derek Stanford, don’t believe cutting other programs would be beneficial.

Stanford said the only thing left to cut are non-discretionary programs, ones that are required by a budget or a contract, such as mental health and prison programs.

He called it a “terrible idea” to cut these and they would be shortchanging Washington state students by decreasing the budget of these programs. And even with these cuts, Stanford continued, there wouldn’t be enough funds to comply with the court.

The state needs anywhere between $3.5–4 billion to fulfill the court orders, a raise from the current $9–10 billion set for education, but if all that were to come from cuts, it’d be “really devastating” to students and families who rely on such programs, Stanford said.

The state is required to pay for nearly everything necessary in a school district. This includes transportation, teacher salaries, technology and most textbooks. However, as Principal Greg Schwab said, Edmonds School District (ESD) is found to not be completely funding all of these requirements.

The state provides ESD with about 77 percent of the cost for teacher salaries, the other 23 coming from the levy, according to ESD Business and Operations Director Stewart Mhyre, however, Schwab said, that is not nearly enough to cover how much ESD employees are actually paid.

That’s where the “levy cliff” comes in.

A number of local levies were introduced in 2015, allowing school districts across Washington state to raise local taxes by 28 percent to supplement things the state does not.

Schwab said that the levies fill in the gap of teacher salaries, along with textbooks and technology needs for students.

However, the “levy cliff,” the name given to the end of levy contracts, will take this away and decrease the amount of money school districts can collect through local property-tax dollars.

This levy cliff is expected to hit Washington state in January 2018 — halfway through the next school year.

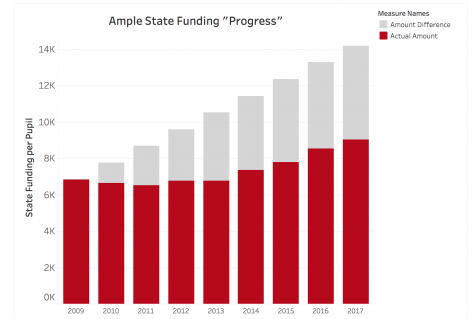

The state expected to have better progress at this time in regards to McCleary, McDuffy explained, but so far that hasn’t gone as planned, she said.

The only problem with the levy cliff, as explained by ESD Superintendent Kris McDuffy, is that this would cause a decrease of $15 million in revenue. And without a clear answer on the McCleary decision, ESD has no way of creating a solid budget. There just aren’t enough answers.

A solution to the levy cliff has a deadline of April 30, but McDuffy said her School Board thinks that is too long to wait.

The annual district budget is expected to be first read on July 11 and finally adopted on August 8 and the Board needs to know how much money they have to work with before April 30. But until then, a number of community meetings are held to propose and prioritize certain programs and Washington state Governor Jay Inslee met with superintendents and legislators earlier this year and expressed that April 30 is simply too late and there should be a plan ready to move forward with how to fill in the gap of the levy cliff by April 1.

There are six budget forums held this year to help plan for next year’s budget. So far, two have been completed, with little movement, McDuffy said.

Two budgets are being proposed for the 2017–2018 school year, Schwab said. One for the “worst case scenario,” in which the levy cliff is fulfilled and the McCleary decision does not fill in the holes and one in which “everything works out” and the gaps dug by the levy cliff are filled.

If the problems posed through the levy cliff are not solved, McDuffy said that the district will have to decrease staff, increase class sizes and extracurricular, district-funded programs would be affected.

Class sizes are a big deal, though, according to Chase. People voted for smaller class sizes, she said, but with the current budget, that’s just not possible.

Chase said Washington state needs smaller class sizes and more classrooms, which would not be possible for most school districts without funding from the state.

Furthermore, Chase thinks teachers salaries should be raised altogether.

She said that most of the teachers in ESD have masters degrees [67 percent?], but she doesn’t believe their pay matches those qualifications.

If ESD has these high standards set for their teachers, she continued, why aren’t they paid well? And why should they stay?

She compared the idea of not paying teachers enough to the women’s suffrage movement and how women fought for their right to vote in 1920, saying it’s up to the people and the teachers to demand a pay that matches their qualifications.

She also compared ESD to Lakeside High School, a private high school in Seattle. Lakeside has a large, upkept campus, they pay their teachers well and have small class sizes of approximately 10–16 students per classroom.

Which is why all the “rich kids” go there, she explained; proper funding leads to quality education.

“It’s not that [ESD] doesn’t know how to teach people, [they] do,” she said. “It’s just about how. Why can’t our public schools have nice campuses like Lakeside? Why can’t we pay our teachers?”

Schwab agreed, saying that he is completely behind raising salaries. He mentioned all the time and effort teachers put into their work, from buying school supplies out of pocket to grading tests and homework on their own time at home.

While being a salaried worker, as opposed to being paid on an hourly basis, on is expected to work past the hours of a normal work day, Schwab said and while the district does their best to compensate teachers outside work hours, it still “nowhere covers the amount that teachers [in ESD] need.”

He continued, explaining how often teachers go above and beyond the expected work, including buying supplies with their own money and buying things for students that they cannot provide for themselves.

Some of this is just a part of being an educator, he added.

“A lot of that stuff [is] hidden [and] people just never see, but it all adds up,” Schwab said.

As for whether these budget changes were to extend to charter schools, a different type of public school that parents can send their children to out of choice, rather than geographical requirements, Chase and Palumbo disagree.

Chase is opposed to additional funding toward charter schools, saying that if she has anything to do with how the funds are allocated, all new revenue would be strictly to the regular public schools.

If people want an education that is an alternative to a customary public school, that’s acceptable, she said, but it shouldn’t be at the expense of the taxpayers.

Palumbo, however, said that charter schools are public schools, just a different form and the McCleary decision would most certainly extend to cover their financial needs as well.

Chase also said that some of the Republicans want to “ignore” the McCleary decision, which she thinks would be dangerous. Palumbo believes some of the members of the Republican caucus simply think the Supreme Court has overstepped their bounds, especially with the heavy daily fine.

But if the Washington state legislature does not continue with trying to find a plan for the McCleary case, the Court could do much worse than implementing a fine.

Moore of NEWS said the state could invalidate the legislature, shut down public schools altogether or even throw legislatures in jail, to which Chase said she doesn’t think it will go that far, but she thinks it should — it’s a crime, she explained, to not follow court orders.

But for those who want a decision soon, Chase continued, they need to rise up. It’s a matter of the people.

“[As constituents], we have to resist the moves that try to say we don’t have to fund our education,” she said.

It’s crucial to properly fund public education, Moore said. The students in public school right now, she continued, are the future.

“If we can’t provide [students] with the best education possible; we’re lost,” Moore said.

The “low budget” set for education affects all of Washington state. While one district may appear to have proper funding and be doing just fine, another is struggling greatly, she said.

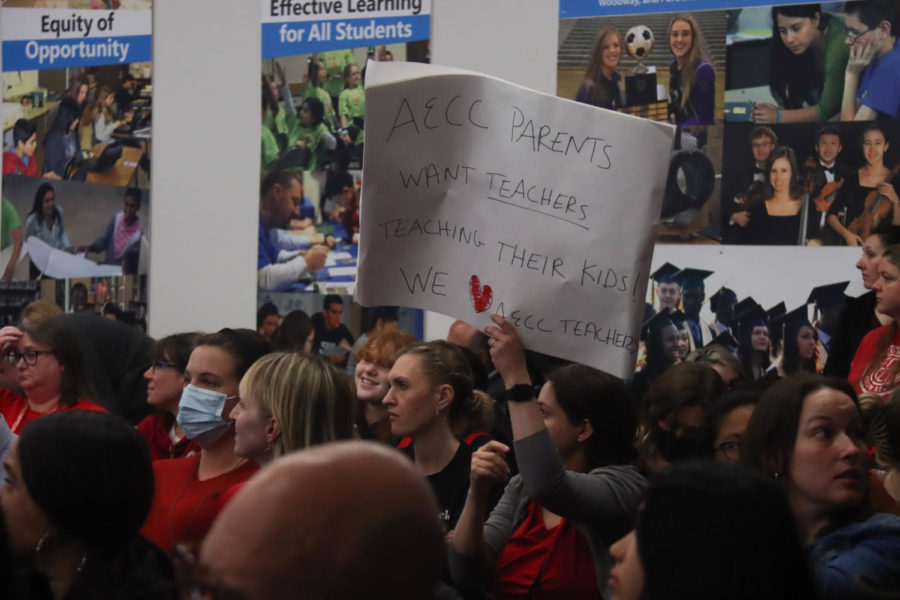

On January 26, Martin Luther King Jr. Day, teachers took to the steps of the capitol building in Olympia, Wash. to protest for better funds of education.

Of the crowd, a handful of MTHS staff attended, including math teacher Nancy Paine, counselor Julie Peterson and science teachers Jonathan Tong and Adam Welman.

“This is the year the Supreme Court obligated to fully fund education, so [educators and voters] need to put the pressure on [the legislatures],” ESD Edmonds Education Association Andi Nofziger said about the protest.

Chase said the protests are held to send a message: all students deserve the very best in education.

Schwab said the protests were vital, along with educating one’s own self on what’s happening in the legislature now.

“We all have a responsibility to make sure people understand; in addition to being educators, we’re also private citizens,” he said.

McDuffy agreed, calling the protests “critical” and “fundamental to a democracy” and that it’s “important to make sure everyone’s voice is heard.”

Moore agreed, stressing on how important it is to see voters practicing their First Amendment rights. She related it to the civil rights era, when black people were oppressed in America during the 1960s and how so much was changed through protests and demands of change.

“I think that’s just how things happen in this nation,” Moore said, referring to America.

Chase said she’s right out there with the educators and Palumbo said it’s encouraging to see voters communicating effectively with their elected officials, as well as putting pressure on them to find a solution.

Whether or not the legislature feels the deadline will be met, it’s rearing up —just shy of 10 months away.

Multiple hearings and financial meetings will be held between now and January 2018, dates to be determined.

Chase said she hopes the constituents and students of Washington state will be pleased with the final decision, but she knows the legislature will have difficulties in the last steps of the process.

Either way, compromise will have to be made by both parties. With any decision that deals with this much money, Moore, Palumbo and Chase agreed, not every party will be completely happy.

“Everyone will have to dig in their heels,” Palumbo sighed.

Moore said she hopes it is completed by 2018 and the Washington state budget will see a change in numbers where it reads “public education” — no matter the difficulties and obstacles faced.

“We don’t elect our legislators based on what’s easy, we elect them based on what’s right,” she said.