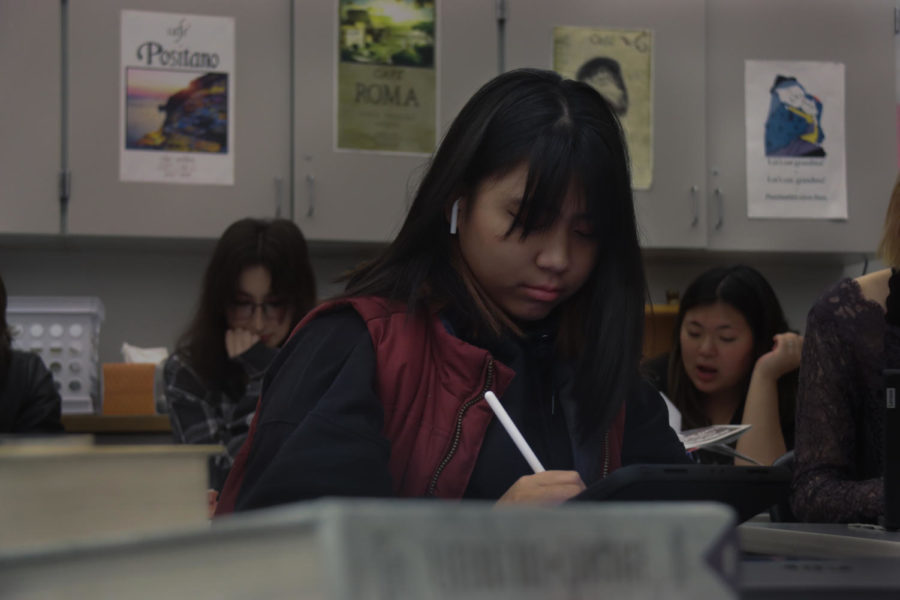

Over the past two years of COVID-19, teachers and students alike have been adapting to the ever-changing structure of learning throughout the pandemic. Teaching methods that were once used so comfortably have been altered to adapt to the challenges posed by remote learning. Standardized testing is one method that has been under heavy scrutiny in the past two years, especially as it became easier for students to cheat on those tests while learning from home.

Although school is back in person, testing is not the same as it was. As teachers work to meet the needs of all of their students, conversations around assessments, and the methods of administering them, have arisen.

Because of the pandemic, students faced a year and a half of isolation from their peers and were left more in charge of their learning than they had ever been before. With that came inevitable challenges.

Many students struggled to maintain the work ethic necessary for good grades, and countless others gave up entirely.

Throughout the remote learning process, teachers had to work overtime to figure out solutions to students’ lack of motivation and feelings of being overwhelmed with the workload. The students’ challenges during remote learning have had a lasting negative impact, and teachers are doing their best to adjust.

“A lot of us have modified our ways of testing,” AP European History teacher Christopher Ellinger said. “Some of us give students more practice before tests, and some have decided to allow notes.”

Ellinger has always seen the final exam for his class as an important assessment, as it is an effective way for his students to better prepare for the AP test in May, while also serving as a progress check for them. This year, however, Ellinger understood that he needed to make some adjustments, especially after a year and a half of online learning.

“A good example of a change is how this year’s final is worth less points than usual. It [the final] was introduced earlier, and with more review, students are able to get more adapted to taking the test,” he said.

According to Ellinger, another way that he and other teachers have attempted to make tests less stressful is by making assessments worth fewer points than they would be under normal circumstances.

”Because of COVID, I began to give fewer tests. The quizzes are not big and there isn’t a big final test at the end of the unit,” Ellinger said. “Performance has been really good on the smaller quizzes and students tend to do better on the less intense quizzes.”

While some classes operate with only Common Core standards to guide them, AP classes must follow AP guidelines provided by the College Board, a nonprofit organization with the mission of expanding access to higher education. Passing the AP exam for each respective subject can earn a student college credit, and AP students spend the entire school year preparing for the test, usually taken during the month of May.

Although AP exams are usually administered on paper, the College Board chose to switch to an online format of the test for its 2020 and 2021 exams. This also created challenges for both the teachers and the students, especially while trying to teach and learn online.

Ellinger described different adjustments made to the online AP test. In 2020, it was reduced to only the document-based question, because the College Board had to change the May assessment at short notice when schools shut down in March. There was also the issue of technical difficulties: some kids’ computers didn’t work, or they had poor internet accessibility.

Motivation levels had a huge effect on the performance of students on the AP exam. Students who had a large incentive to do well on the AP test worked to earn that grade, but without that motivation, or the interactive preparation methods, it was much more difficult to both teach and learn the information at the level needed for the AP test.

“I’ll take my hat off to last year’s kids. The kids who wanted to do well and perform, they found a way. And not just because of COVID or the way the kids work,” Ellinger said. “I wasn’t able to provide the same type of test preparation methods; we couldn’t do Quizlet Lives or reviews. But the scores were comparable to pre-COVID scores. That’s a testament to how hard kids worked last year.”

While many students did their best to work through the challenges of remote learning and to understand their class material, many others resorted to the less honorable, yet easier, way of cheating. Although it has always been present, Ellinger found cheating became more of a problem than ever during remote learning. On top of the natural challenges of teaching last year, cheating added on even more work and thought that had to be put into each assignment.

“Seeing all the cheating was depressing – it was hard to prevent because students figured: “Why not?” and then it was hard to redesign a test that could prevent it,” Ellinger said. “I didn’t have the time or the energy to do that, and I don’t think that was the best thing to do either. It wasn’t just on tests, it was on assignments too.”

This cheating mentality has carried over into this year, making tests and assignments difficult for students.

“If that was the way you operated last year, and now you try to operate like that this year it’s not going to work the same,” Ellinger said. “When I’m making projects, I have to think: how cheatable is this assignment?”

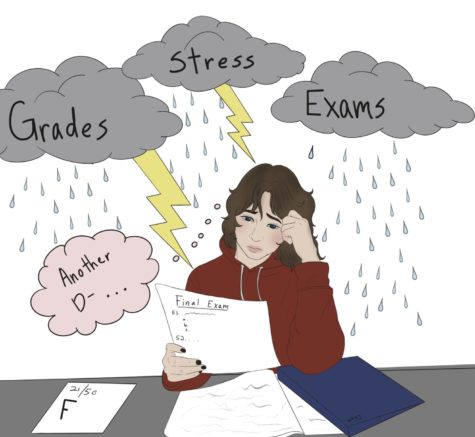

Much of this incentive to cheat came from the building pressure to maintain good grades last year, which proved to be a struggle.

“I can see how it would be easy to cheat with the internet readily at our fingertips,” sophomore Reese Krieger said. “Since COVID started, I felt more and more pressure to do better in school.”

She went on to talk about how last year seemed especially stressful in terms of grades and school work, and combined with the loss of motivation, it made it much harder to put in the effort.

With the return to in-person school, some students are feeling the effects of last year’s asynchronous learning. After spending a year and a half online, in which motivation levels were low and cheating was easy, tests and time management have become difficult.

“Kids are more overwhelmed by the idea of a big test because they didn’t have one last year.” Ellinger said. “Kids this year struggle with how to maintain the time to prepare for a big test.”

After years of preparing students for the AP test, Ellinger said that this year has been a different kind of challenge. In addition to AP European History being their first AP course, his students are sophomores, meaning they experienced their entire first year of high school online.

Freshman year is often used as the transition year from middle school to high school, so the absence of that transition has been one factor for the lack of practice and the higher anxiety revolving around school. This was the case for Krieger.

“Maybe it is just that I am a sophomore and I am experiencing in-person high school for the first time,” Krieger said. “I feel like this year has been a bit rushed with all the tests.”

Krieger also said that she feels like tests should be administered differently than they currently are. She has found that having flexibility in the time she takes on her tests has helped her performance, especially since she doesn’t consider herself a good test taker.

“I personally feel like tests shouldn’t count for as much of our grades as they do, because if someone does all the work and does bad on a test, all that hard work they did is disregarded,” Kreiger said. “I don’t appreciate when tests are super big parts of the grade either, because some people don’t do as well under pressure, and it isn’t a fair representation of their skill.”

For an AP teacher like Elllinger, it is important to prepare the students for what they will encounter on the AP exam, while also taking into account the different learning styles.

“I’m an AP teacher and I have to be honest,” he said. “The AP test is pretty traditional. It doesn’t really speak to different styles and that’s why I try to do big assessments that are varied. I’ll have the paper text, the debate, the salon discussion, those are big [assessments]. You’re demonstrating your understanding of a subject.”

For AP classes, class assessments are an essential tool for preparation for the AP exam. However, the last two years of less intense testing has resulted in greater test anxiety upon returning to school in-person.

For Ellinger, one of the biggest obstacles has been reintroducing tests to students. Test taking is a skill that he said everyone needs for all aspects of life, and after two years of nontraditional testing, students are more anxious than ever.

“Unfortunately, over the last couple years test anxiety has risen and kids get overwhelmed at the concept of a test and different types of testing, so we need to help folks to address it,” Ellinger said. “I still think there is value in it, life is full of tests not just paper and math but challenges and things that require us to prepare for it.”

Beyond school, people have to prepare for life skills like job interviews, driver’s license tests and college applications, which underline the need for learning test preparation skills in school. However, Ellinger said, a way to offset the need for skills from the anxiety of tests is to have tests not be worth as much of a grade.

“I don’t believe in tests that are the end of the world,” he said. “Tests have value for that reason and it should be a part of that class but not dominating.”

According to both Ellinger and Krieger, flexibility in testing methods such as smaller quizzes, allowing notes and more time could all improve the assessment of student learning. The key for success is communication between students and teachers to make sure that all learning styles are met.