Imagine one day, you wake up to find the world has been stripped of all color and shape. All you are left with is the light of day, the darkness of night and the outline of a person if they are standing right in front of you. If you can imagine this, then you are imagining how I see the world every day.

As I grew up in a predominately sighted world, I quickly realized I had something to prove. No one in my native country, Nepal, had ever been around a visually impaired person. I was “different.” No one knew what to think, how to act, what to expect. There weren’t very many people who thought I could make anything out of myself due to my blindness.

Ever since I was little, the thing I wanted most was to go to school. I saw it as my one chance to prove to anyone who had doubted me that I could make something out of myself. Out of the 15 or so Nepali schools my family and I looked into, only one was willing to accept me.

All of the hope I had been holding onto shattered at that point. Maybe everyone had been right. Maybe there really was no place for me in the world.

“But why?” my three-year-old brain asked itself. The answer was just as unsatisfactory each time: “Because you can’t see.”

At the age of four, I was brought to the United States to see if anything could be done for my vision. That’s when I was diagnosed with Leber Congenital Amaurosis (LCA).

LCA is a retinal disease in which little to no light can be perceived. The disease is usually present at birth, but only about one in every 100,000 children are born with it. There are about 20 different forms of the disease and only one person with each form at any given time, making it difficult for doctors to test for cures.

Though gene therapy (a surgery in which the necessary gene is injected into the eye) has cured a few forms of LCA, a lot of research is still being conducted for the many forms not cured yet.

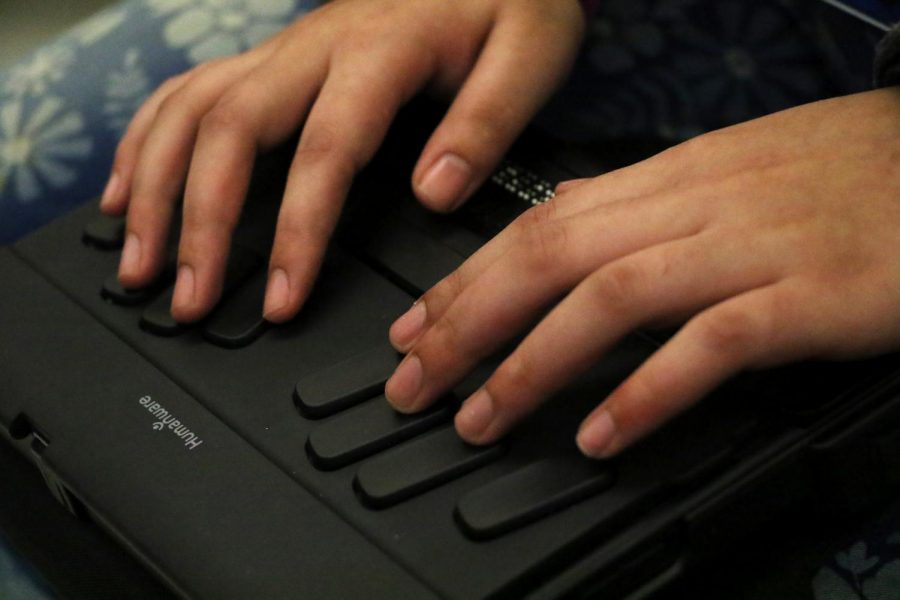

When I first came from Nepal, I couldn’t see how I was going to fulfill my dreams of going to school. Two months into my first year at Hazelwood Elementary, however, I had discovered the miraculous world of braille.

I was now on the same playing field as my peers. It no longer mattered that I couldn’t read and write with my eyes, because a six-dot code gave me the chance to do it with one fingertip. My dream of going to school and learning with my peers was coming true, and I was hungry for more.

By third grade, instead of using an eight pound braille typewriter for assignments, I found myself typing up my assignments using an Apple wireless keyboard and a built-in accessibility feature called Voiceover on an iPad.

Soon, I was learning to use different screen readers on computers, printing my assignments from a braille tablet, and mixing technology to do all of my school work.

I can’t say that having a visual impairment doesn’t have its challenges. Little things that are normal to the rest of the world can be huge challenges for me. For example, most people don’t spend weeks learning how to navigate a new environment. Most people don’t find it difficult to hop on a website to research an assignment. Most people don’t have insecurities about moving from point A to point B for the fear that one little veer could lead to a completely unknown space.

Sometimes, overcoming the challenges can be exhausting, but I’ve found there is always a way to get around those challenges if I want something enough. However, it truly does take a village, and I’ve been extremely fortunate to have incredible support from all fronts throughout my years of school.

For as long as I can remember, I’ve always had at least one Braillist who converts material into Braille when I need it, and an orientation and mobility instructor who helps me learn to navigate the physical world independently. I’m also extremely fortunate to have peers who accept me for who I am, and incredible day-to-day teachers who do everything from modifying assignments to describing videos the class is watching.

Without their support and encouragement, I would never be able to get past some of the obstacles I face, and I am always grateful to them for all they do.

When I meet people for the first time, it can be hard for them to know how to act around me. Without even realizing it, they often either talk to me as if I can’t hear, ignore me completely or direct their sentences towards whoever is closest to me.

When you have had something all your life, it’s hard to imagine life without it. Therefore, I know people are curious about how I do what I do. Most people feel weird asking me about something related to my blindness because they think the question might be offensive or a “stupid” one.

As they get to know me though, they discover I am very open to questions and will answer anything.

Just like it’s hard to imagine life without something you’ve always had, it’s hard to imagine life with something you’ve never had. I’ve never had sight, so while having it would make things easier for me, life without it is the only life I know, and I see it as a chance to change the way the world sees people with disabilities.

I see it as a chance to educate others and show that at the end of the day, we’re all humans, and we’ll always have that in common.