After the 2016 presidential election, more than 100 students participated in a nationwide walk-out to protest the new president elect. Students struggle to have much of a voice in politics being under the age of 18 and unable to vote.

“Know your rights,” say The Clash in their protest song of the same name, which highlights differences they observed between the rights — the right not to be killed, the right to food money, and the right to free speech — that people seem to have and the rights that are actually enforced. Students, like The Clash, have the right to protest injustices they see, as long as, according to assistant superintendent Greg Schwab, they protest at an appropriate time, in an appropriate place, and in an appropriate manner.

In regards to students expressing their views; time, place and manner is what keeps them acting in civil disobedience rather than disrupting the school day for others.

“Students have the right to execute their First Amendment [rights] and that includes doing protests and walkouts. The thing that they can’t do is disrupt the operation of school,” Schwab said.

In the past few years at MTHS, students have been viewed expressing their First Amendment rights, causing more staff and students to notice the changes. Whether it’s sitting during the pledge or national anthem, walking out or wearing their political opinions on their sleeve, students have been speaking out for what they believe in.

The real question is how far that can go.

“It’s that disrupting school line. If you’re doing something that disrupts the normal operation of school, then you’ve probably crossed that line.” Schwab said.

Protesting

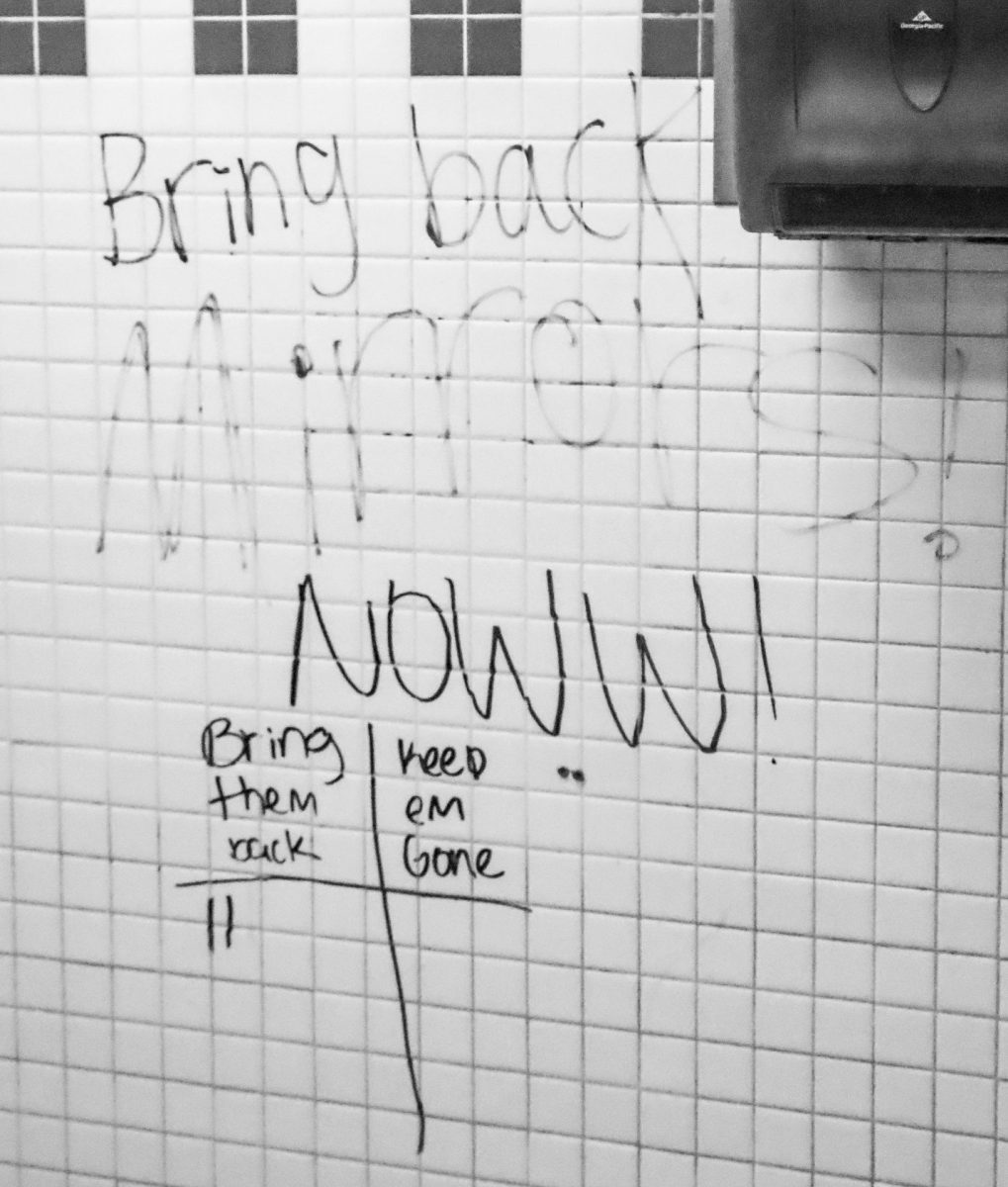

The “Not My President” walkout on Nov. 14, 2016, the walkout in solidarity with Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School on March 14, 2018, the “National School Walkout” on April 20, 2018; these national walkouts took place at MTHS, all organized by students.

According to the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), students are allowed to organize protests, but schools have the right to discipline studentswho fail to follow the time, place and manner rule. So, students should be able to organize movements outside of class or during lunch. As long as the protest doesn’t disrupt school, such as blocking the halls, the school or interrupting class time, there isn’t much the administration can do.

Back in March, the Superintendent of the Needville Independent School District sent a letter to families informing them that students faced a three-day suspension if they joined the March 14 national walkout.

Schwab held the question, “would you normally suspend a student for skipping a class?” In reality, the ACLU said that schools cannot punish students more harshly for a walkout absence than they would any other absence.

Altogether, this means that for a first-time unexcused absence, a school cannot suspend a student.

The ACLU states that when a student gets an unexcused absence, “the law requires districts to try other interventions (like attention or a conference with your family),” before suspension.

“What schools can do is they can hold students accountable according to whatever their policies or procedures are with regards to attendance,” Schwab said. “I think where our district has landed is that we’re going to mark students absent if they choose to participate and then it will be a parents’ decision on whether or not they want to excuse that absence.”

Along with that, Schwab said that after a walkout, the student who participated would have to go through “whatever the normal punishments are for an unexcused absence.”

The Pledge and National Anthem

Whether a student is one of the few who sit during the National Anthem, or one of the hundreds who sit during the Pledge of Allegiance during school, the rights are fairly simple.

“What the law says is that students must maintain a respectful silence, that’s all it really says. It doesn’t say that you can’t take a knee,” Schwab said. “What you can’t do is prevent or interrupt others choice to recite the pledge.”

The law of respectful silence also falls under the National Anthem. So, students are legally allowed to sit or take a knee as long as it doesn’t disrupt another student who is reciting it.

The ACLU said that “students cannot be forced to make a pledge of loyalty to the government.” With this, staff members are not allowed to require students to say the pledge or stand during the National Anthem.

“That [law] has been interpreted many ways. But, again, choosing not to stand is mostly what we see happening. You just can’t disrupt the pledge.” Schwab said.

Many MTHS students do not stand for the pledge as observed in different class settings. This group includes freshman Katie Barry, who said that she doesn’t stand because “everyone should be equal but no one is being treated equally,” in regards to the line “with liberty and justice for all.”

Although staff are not allowed to require students participate, Barry said that she has experienced different substitute teachers taking matters into their own hands.

“At my middle school [and] my elementary school we didn’t actually have the Pledge of Allegiance, so this is like a new thing going into high school. None of my teachers currently this year have told me to stand for the pledge, they’ve just told me to be quiet,” Barry said. “But, some [substitute teachers] have told me that I should stand for the Pledge of Allegiance because I need to respect America.”

Barry said that her friends have been affected by substitute teachers as well.

“There have been teachers at my friends schools, like at Lynnwood high school, that have had [substitute teachers] that have written them up if they hadn’t stood for the pledge.”

Political Expression and limits

In December of 1965, 13-year-old Mary Beth Tinker and a group of her friends went to school wearing black armbands to protest the Vietnam war. School administrators asked her to remove the armband and, when she said no, she was suspended with four other students.

The suspended students were not able to return to school until they removed their armbands. These students, represented by the ACLU, started a four year battle landing in the Supreme Court as Tinker v. Des Moines.

This case is what officially gave students the right to free speech in schools. On February 24, 1969, the Court ruled 7-2 in favor of the students.

“It can hardly be argued that either students or teachers shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate,” Justice Abe Fortas said.

The Court ruled that public schools still had to adhere to the First Amendment and administrators could not censor student speech unless it disrupted school.

This means that the armbands that Tinker wore are protected by students’ First Amendment rights and that students are still legally allowed to express their political views in public schools.

Protected speech includes wearing buttons, armbands, shirts or other clothing and accessories with messages or writing in the school paper. Schwab said that handing out printed petitions or flyers in school, so long as it is not advocating for illegal activity, is also protected as students are not forced to accept the paper.

Despite students’ First Amendment rights being protected, there are ways for schools to prevent or punish students. According to the ACLU, schools can place “reasonable restrictions” using time, place and manner to restrict speech.

For example, if what is being said will cause “substantial” disruption or is advocating illegal activity, student speech is not protected and can be disciplined.

Along with that, student speech is not protected if it’s considered libelous, meaning that, according to the ACLU, “it is untrue, harms someone’s reputation, and you know or should have known it is untrue when you say it.”

Many topics can come up in conversation between friends and peers in school, but some can be deemed “too controversial.” From the day’s lunch to war, or budget cuts to Planned Parenthood, students can get into heavy conversations in the halls.

Even though these topics can potentially make people uncomfortable, public school administration is not allowed to censor student speech based on the topic, regardless of how controversial it is. Unless the speech will “cause a substantial disruption,” the ACLU said that “criticism of your school, teachers, or school officials, or discussion about serious problems either at school or elsewhere is generally protected.”