Making the Decision

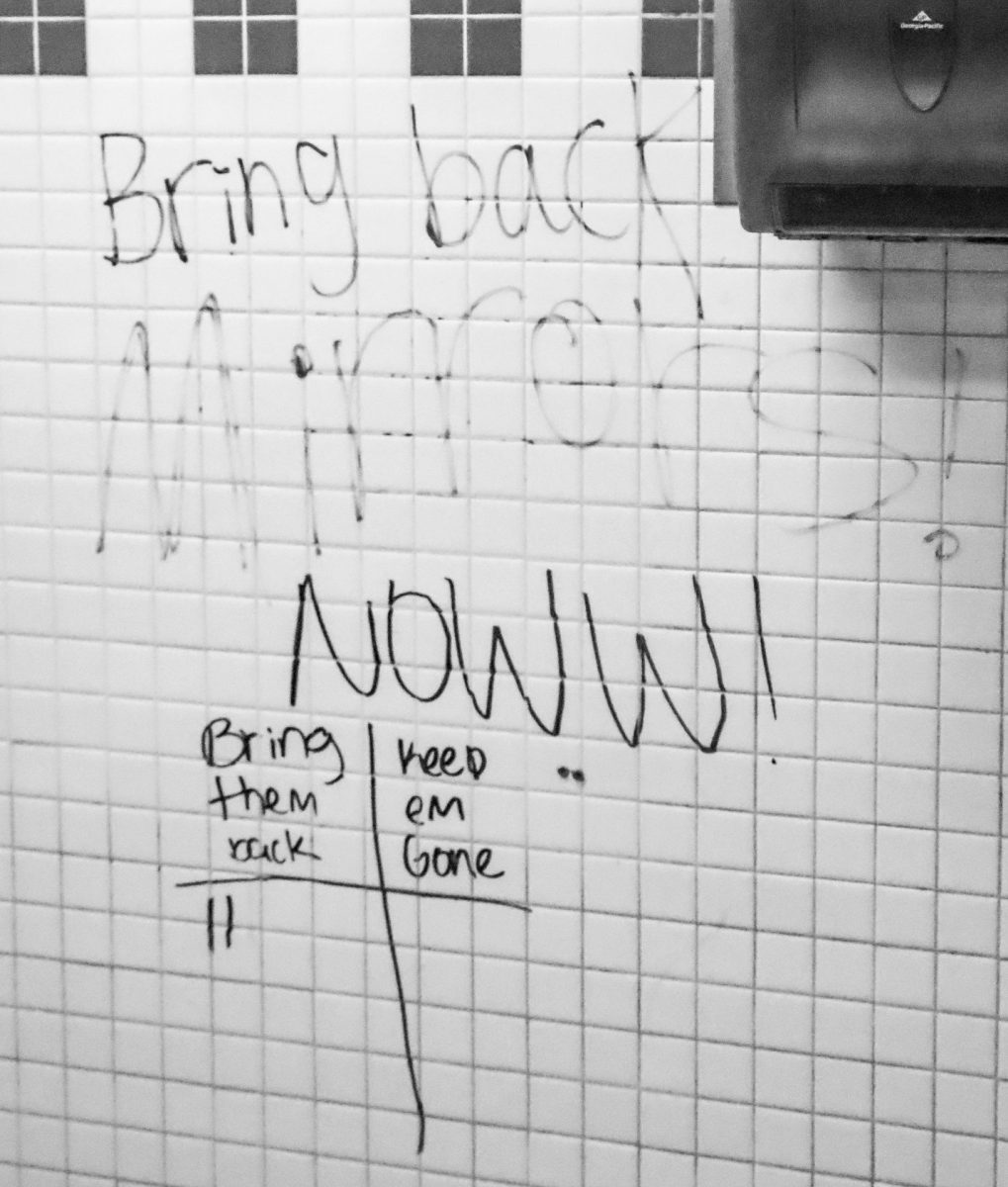

Feminine hygiene product (FHP) dispensers are being reinstalled in girls’ bathrooms to increase their accessibility, following a decision by the staff and administration. MTHS formerly had these dispensers, which provided pads and tampons, but removed them due to vandalism on the machines.

According to former principal and current Assistant Superintendent Greg Schwab, MTHS “had several instances of the products being removed and used to plug toilets as well as having the dispensers torn off the walls.” It became too difficult to consistently replace the FHP and dispensers, leading the school to elect to remove them around 2007 or 2008. From then on, the distribution of feminine products became concentrated to the Health Room in the main office.

Currently, if a student needs to obtain hygiene products, they can follow a short procedure in the Health Room. Students only need to ask to use the health room bathroom, which carries various feminine products; they do not have to specify what they need or request them by name.

Reimplementing tampon and pad dispensers in bathrooms was a building decision made by the Interim Principal Greg Schellenberg and office personnel. The decision was based on the cost to support the dispensers and consideration of how they are treated and used. An order for two FHP dispensers was placed in December before the holidays.

According to former student support advocate and social worker Ashley Dawson, none of the current MTHS administrators knew why the dispensers were removed from the bathrooms. However, Schwab shed some light on their backstory, explaining that administration elected to remove feminine product dispensers due to significant vandalism.

District maintenance offers the option to reinstall dispensers if a school has a need or desire for them during any time of the year.

Aside from the Health Room, Dawson occasionally helped provide FHP to students in need.

“My role is primarily for students who do not have access to [feminine] products due to a financial barrier. That tends to be the biggest reason why I would be involved so I’m able to help students get a product that they need if they’re not able to afford them,” Dawson said. “Every so often there might be an emergency where I might step in if any person forgets something or needs something then I have quite a few available.”

Most of the school’s feminine products come from donations from organizations such as Washington Kids in Transition and the Nourishing Network under the Foundation for the Edmonds School District, as well as supplies received from the annual Key Club toiletry drive.

Dawson stressed the importance of providing easy and open access to students who need feminine products. “I think it’s something that half of the population in our school needs at least once a month for a long period of time in the month. Having accessibility means removing the barrier of having to ask for it or having to search for it,” she said. “I think as any woman knows, it’s an emergency when you need one so at least that they’re readily available is important.”

In order to increase accessibility to feminine products, Dawson said it would “make most sense to reinstall the tampon and pad dispensers in the bathrooms.” With that, Dawson was dismayed upon learning why the school removed the dispensers.

In order to increase accessibility to feminine products, Dawson said it would “make most sense to reinstall the tampon and pad dispensers in the bathrooms.” With that, Dawson was dismayed upon learning why the school removed the dispensers.

“I think it’s disappointing that they were removed, but I understand the reason why and I think that’s what disappoints me more is that so much vandalism was happening because FHP dispensers are a resource and the very people who are using them are also the people who are vandalizing them,” she said.

Family & Consumer Health teacher Kimberly Nelson said she hopes providing more ways of feminine product distribution will reduce the stigma around discussing the topic.

“That has a possibility of being psychologically challenging for a girl and it’s not socially acceptable to ask for it in class, ‘Hey does anyone have a tampon I can borrow?’” Nelson said. “I don’t understand why there’s shame involved; it’s not like you’re doing something wrong. Your body’s doing what it’s naturally supposed to be doing. We don’t always have the ability to control that. If we did, the world would be a different place.”

Nelson personally stocks up on these items in her classroom to give to students in need; some of these products come from Key Club, as she is the club’s adviser. She said she believes students should be able to obtain feminine products from bathrooms and not just the Health Room bathroom, which would be achieved by reinstalling the dispensers.

Nelson predicts the possibility of vandalism can be prevented if girls learn the reason behind the removal of the dispensers and recognize the significance of having dispensers available in the bathrooms and shape up their behavior in bathrooms.

“I think this is a great idea. If girls knew the reason they don’t have [dispensers] now is because of vandalism in the past, knowing how it’s been a challenge now for girls, maybe girls will be more responsible about their behavior in the bathroom,” Nelson said.

“I think if girls understand that’s why we didn’t have it, that perhaps things would change because you know, it’s been a while and maybe girls have matured a bit and maybe it’s just not that big a deal anymore,” she said.

As reinstalling dispensers is a building decision, the choice falls in the hands of the Steering Committee led by Schellenberg. This group is comprised of department heads and other staff in leadership roles at MTHS, including Nelson.

The Steering Committee made the decision after considering input from Dawson, school nurse Julie Hill, the assistant principals and custodial staff. In addition, they had to regard the financial impact of installing and refilling the dispensers.

“Every cost has a benefit to it, too. It’s that analysis that makes it whether it’s a worthwhile endeavor to take on. Some costs are worth it,” Schellenberg said.

Schellenberg sees value in ensuring students are comfortable and confident at school and believes reinstalling dispensers can reaffirm this sense by providing “a variety of locations” within the building that supply feminine products with “greater privacy and quicker access.”

“Equity is such a keyword right now, an important word. Any practice or lack of practice that we have that makes people feel marginalized needs to be looked at,” Schellenberg said.

According to office manager Cathy Fiorillo, the school made the decision to reinstall dispensers for students “to save the trip of having to go to the main office and ask [for FHP].”

“I am a strong believer in equity. We’re a public service. We’re here to suit student needs,” Fiorillo said.

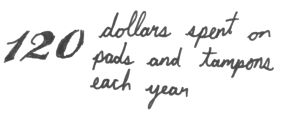

She is looking into how these products can be provided for free as they are typically available for 25 cents in dispensers.

Next Steps

The school plans to move forward with the feminine product dispensers by installing two units, priced at about $240 each. Head Custodian Darren Sheehan determined the most frequently used girls’ bathrooms to be the two closest to the HUB.

Jonathan Kwong

Jonathan Kwong

Fiorillo envisions the machines as dispensing one product at a time. She is an advocate for making the products free, but is also seeking a way for students to optionally pay for them if they so choose, with the products being at cost.

Though MTHS will pay for the feminine products out of the building budget, Fiorillo has no intention of making a considerable profit off of them. She compared FHP to being as essential as toilet paper.

“I felt like if we had a toilet paper dispenser, would they just remove the toilet paper if there was vandalism?” Fiorillo said. “To me, [FHP are] a need and it’s a little different because women purchase their own. You wouldn’t bring your own toilet paper and paper towels to school.”

While administration wanted a dispenser in every girls’ bathroom, the cost would have amounted to more than $1,000 which they deemed unsuitable for their budget. Fiorillo considers this decision to be a pilot test and administration may incrementally add more dispensers if the first two are well received by the student body.

Fiorillo said she cannot predict how the general community will treat the dispensers, however she generally has no concerns regarding the usage of them.

“It’s your school, it’s your bathrooms, they’re just doing damage for themselves. I would hope this would be something students would say, ‘This is for us so let’s take care of it,’” she said.

Fiorillo intends for the dispensers to be used for emergencies or when a student is truly in need of a FHP.

If a student needs a stock or supply, they are encouraged to talk to new social worker Latisha Williams about an alternative method of acquiring them. Williams began her first official day of work at MTHS on Jan. 8, but already has a solid view of how she will help students access menstrual supplies.

“I think my role is to find [FHP], help students find them, make them readily available, I think is the best way for me to put it. If that’s a need that’s in the school and a need for students, then that’s my job to help support that need and help figure out how to meet that need on a long-term, more sustainable basis,” she said.

Williams broadened the audience, seeing menstruation as a situation everyone faces in some way, thus reinforcing why she supports the FHP dispensers.

“Everybody, I think no matter how much money you have or how much money you don’t have, not that people are forgetful, but you always have a time where you’re like ‘Hey, do you have…’ I think the benefit of that is that it’s supportive to the whole school, not just to the people who don’t have the resources to access tampons or pads on an ongoing basis,” Williams said.

“Everyone at one point or another in their life, finds themselves in a situation in where they don’t have what they need and so to have it on campus readily available can only benefit us and I think that outweighs any cost that we would accrue from taking it on at the school.”

Installing dispensers furthers the school’s goal by providing more points of access to FHP so students can more quickly and subtly receive them. Fiorillo views a lack of accessibility to not only be a health obstacle, but potentially an academic one, too.

“It’s something that can get in the way of education. [The goal is] to remove any barriers that students would have to access education and that is a potential barrier and a stress,” Fiorillo said.

“If a student starts her period in the middle of the bathroom, to have that convenience be right there [takes] away the stress,” she said.

Similarly, Williams also finds that limiting methods of obtaining FHP troubles students because they should be able to satisfy unavoidable needs instead of encountering roadblocks in doing so.

“It’s human nature, I think is the most transparent way I think I can say it. It’s a need that everybody has and I think everybody should have access to it. I think not having [FHP] creates barriers and those aren’t barriers that we need,” Williams said. “I think that need has to be met in order for students to feel supported in school.”

In the meantime, Fiorillo will continue researching how other school districts manage their FHP dispensers.