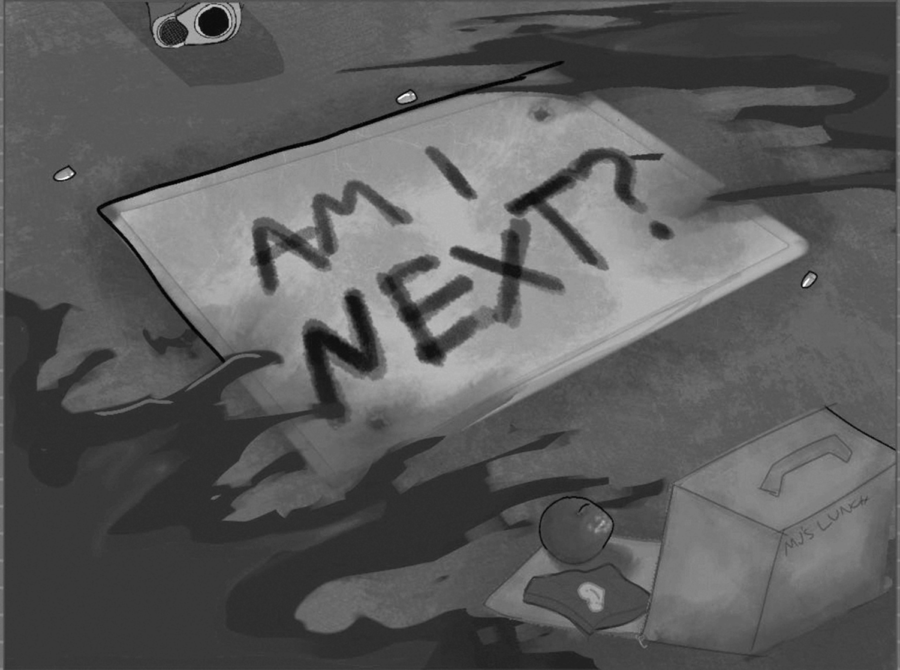

It’s safe to assume most students don’t go to school expecting to not return home. But in this day and age, it’s hard to not be aware of that possibility every now and then—even more so, depending on where a student goes to school.

The most recent school shooting to date in the United States was two weeks ago, on April 10 at North Park Elementary School in San Bernardino, Calif.

Before that, there was a misfiring at the University of St. Thomas in St. Paul, Minn. on April 7 (no injuries or fatalities). And on March 31, a gun was fired at the University of West Florida in Pensacola, Fla. (no injuries or fatalities).

America is no stranger to school shootings.

Since 2013, Everytown, a nonprofit organization advocating for gun control, has worked to understand and reduce gun violence in the U.S. The organization has listed over 200 cases of gun violence in schools since January 8, a number inclusive of intentional, unintentional, fatal and non-fatal acts as well as acts of suicide.

That’s about four years worth of weekly school shootings.

While not all of them may have resulted in injury or death, the shooting at North Park did. 8-year-old Jonathan Martinez and another student were caught in the line of fire while standing behind their teacher, 53-year-old Karen Elaine Smith.

Smith was the estranged wife of Cedric Anderson, also 53. Anderson had gone to the school campus to drop something off for his wife, and upon entering the classroom Smith taught in, Anderson opened fire.

Smith died and Anderson shot and killed himself. Martinez later died from his wounds; the other student shot is in stable condition.

Hearing about another school shooting hits local; Marysville-Pilchuck High School, just north in Marysville, stood under the national spotlight when four students and the perpetrator were shot and killed in the campus’ cafeteria. The only survivor was student Nate Hatch, who was injured.

Remembering the victims

It’s been just over two years since the shooting at Marysville-Pilchuck. Isaiah Galindo, a sophomore at Marysville-Pilchuck wrote, “People don’t talk about [the shooting] right [now] and it’s slowly being forgotten.”

But, forgetting the shooting plays directly into the fears of those from Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Conn.

On December 14, 2012, Sandy Hook was the scene of a high-profile mass shooting. 27 lives along with the life of the perpetrator were lost.

“We’re all terrified of forgetting what [Ben] looked like and what he sounded like, so I will go back to a video or a picture or something just to—you know, to have him back,” Dave Wheeler said in ‘Newtown’, an independent documentary by the Public Broadcasting Service.

‘Newtown’ was filmed over the course of three years; directed and produced by filmmaker Kim Snyder, it runs nearly an hour and a half and is full of stories from the day of the shooting.

“Through raw and heartbreaking interviews with parents, siblings, teachers, doctors, and first responders, ‘Newtown’ documents a traumatized community still reeling from the senseless killing, fractured by grief but driven toward a sense of purpose,” the film’s website reads.

Dave Wheeler was the father of Benjamin Wheeler, one of the children who died that day. Benjamin Wheeler was 6 years old, as were the majority of the victims; 20 of the victims were first graders.

Tammy Reardon is a first grade teacher at Terrace Park Elementary.

Despite the outcome of Sandy Hook, “I don’t think I’ve ever thought, ‘Oh my goodness, that could’ve been me, or it could’ve been my students’,” Reardon said.

“Initially, you’re just shocked. I just can’t believe that anybody would go in and hurt children, and especially with Sandy Hook, children that are that young. I think I’ve thought more about, y’know, ‘What would I do?’”

The numbers

Maybe it’s unjust to compare North Park to Marysville-Pilchuck to Sandy Hook. While in all cases the perpetrator died, North Park had two casualties, Marysville-Pilchuck had four and Sandy Hook had 27.

It’s arguable that the impact of the shooting would change with the number of casualties, but those numbers don’t change the fact that those who died were people. They had lives, stories and names, which can get lost in a plethora of data.

Monsignor Robert Weiss from St. Rose of Lima Church in Newtown was one of the people tasked with telling families after the Sandy Hook shooting their child had died.

“It’s – It’s fearful, you know, it’s really fearful that people’s lives can be so disrupted so quickly forever. There’s no making up for this. The foundation got cracked, and everybody’s not certain how wide that crack is going to get,” Weiss said in ‘Newtown’.

Blaming

Some people find sense in blame, and in blaming the weapons themselves: the guns.

In 2009, Ohio University Professor of Psychology, Dr. Mark Alicke, worked with Dr. Ethan Zell, assistant professor at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, on an article published in the Journal of Applied Social Psychology about blame.

“If ‘to forgive is divine,’ then to blame is mundane,” the article says. The work argues that blame comes from primitive roots.

Alicke and Zell take an individual who “kicks the refrigerator for stubbing his toe” as evidence that humans tend to treat inanimate objects as able to injure someone out of free will, making them “eligible for blame”.

Whether it’s the revolver used at North Park, the handgun from Marysville-Pilchuck, or the pistol and rifle used at Sandy Hook, many individuals use the weapons from mass shootings as grounds to push for more expansive gun control.

For example, Australia’s Port Arthur Massacre in 1996 led to the tightening of rifle control laws. Later in 2002, after a shooting in Melbourne, handgun laws were also tightened.

Australia’s gun control laws include a federal ban on the importation of various firearms, the requirement of different permits per weapon, restrictions on the amount of ammunition given in a certain period and requires a “genuine reason” for why someone wants to own a firearm.

And while the cause is up for speculation, Australia hasn’t seen a gun-related mass killing since 1996, compared to the United States which has seen them nearly weekly since 2013.

Pew Research Center found that “Americans have shown broad and consistent support for expanded background checks for gun purchasers.” In 2015, 85 percent of the public were in favor of background checks, including 79 percent of Republicans and 88 percent of Democrats.

The Center also found that protection, rather than hunting, was why most people owned guns.

In 1999, 46 percent of gun owners said they owned guns for hunting compared to 26 percent who owned it for protection. 14 years later in 2013, the percentages changed by double digits: 32 percent of gun owners said they owned guns for hunting while 48 percent said their guns were for protection.

Protection is the argument Michael Newbern, the Ohio Director for Students for Concealed Carry makes.

Newbern used to serve in the military but didn’t usually work with guns. After finishing his service, Newbern moved to Ohio, got his license for a concealed handgun, and found he wasn’t allowed to carry his concealed weapon on college campuses.

“But I started seeing students be assaulted… being victimized, and I thought that was wrong. So I decided to restore their right to choose to defend themselves,” Newbern said.

Newbern stressed that if an individual is a law-abiding citizen who is licensed to carry a concealed weapon, they should be able to carry their concealed weapon onto a college campus.

Students for Concealed Carry (SCC) works to allow this. Their argument, as stated on their website, is that licensed individuals should be allowed to carry concealed weapons onto a college campus due to it being a “legal entitlement to self-defense” and in the case of “actual need for self-defense”.

For opponents of SCC’s cause who believe concealed carry could lead to negligent/accidental discharge, SCC notes that within the over 150 college campuses allowing licensed concealed carry, only three have led to unintentional, non-fatal, discharges: two being failure to carry the gun without a holster and the other being a licensed holder showing a student unfamiliar with the gun how to use it.

Washington state allows schools to determine whether or not to allow licensed concealed carry on public or private college campuses.

Regardless of one’s opinion on the potential use of guns and weapons as a preventative measure, for some, choosing to blame weapons, or to turn to them for protection, is how they make sense out of a senseless tragedy.

Rebuilding

For Marysville-Pilchuck and Sandy Hook, their sense of it all comes out of rebuilding.

The cafeteria where the Marysville-Pilchuck shooting happened hasn’t been used since. It’s still standing, too, due to a bond measure that was supposed to help with demolishing it failing in November.

What the school has done is built an area called the Commons, which was first shown to the public and toured by Governor Jay Inslee on March 28.

Marysville-Pilchuck has partnered with a variety of organizations including UW Medicine in efforts to counsel and train those in the community to recognize signs of depression, anxiety and substance abuse. The school has also been given grants with $3 million for mental health, suicide and substance abuse counseling.

Newtown spent nearly $1.4 million demolishing and on the abatement of Sandy Hook. Last year, the new school building was opened in a different area of the same land the first building was on.

Designed by Svigals & Partners of New Haven, the new building is calming while also providing comprehensive yet subtle safety measures.

Doors can be locked from the inside or outside so in the case of an intruder, teachers can protect students without having to open the door. Side windows neighboring any classroom doors are bullet-resistant and the interior walls are reinforced.

The healing process isn’t just physical: Rick Thorne, janitor at Sandy Hook, was asked how he got through his days in ‘Newtown’.

“The kids. The kids at the school. The laughing, the smiling,” he said.

As Sandy Hook and Marysville-Pilchuck take the appropriate actions in healing, other communities follow their lead in anticipation and preparation as a precaution.

“I think we’re doing all that we can do—I think as a school community we are. And I think the district is as well,” Reardon said, regarding if she thought enough precautions were being taken in the school community.

Security experts have come to the district to train community members and school staff on the ALICE system. ALICE stands for Alert, Lockdown, Inform, Counter and Evacuate; it’s a strategy being adopted in schools across the nation in the case of an active shooting.

At Terrace Park, staff have been more cautious themselves in keeping classroom and exterior doors locked and in keeping an eye out for strangers who might come on campus.

“I’m not scared, at all. I think we’ve all become a lot more vigilant,” Reardon said. “We’ve just taken steps to be safer than we were before.”

North Park has many ways and time to heal. North Park has all the time in the world to heal.

There’s a lot that goes into moving forward, but it’s not impossible.